At a time when the concept of masculine energy is manifested in unfortunate ways (think chainsaws cutting aid for the starving), I see a bright spot: his name is Nicholas,…

At a time when the concept of masculine energy is manifested in unfortunate ways (think chainsaws cutting aid for the starving), I see a bright spot: his name is Nicholas, and he’s my son.

He’s also now the father of three girls, my rambunctious and adorable granddaughters. Let me tell you about his masculine energy.

Nicholas is a baker.

Not just any baker, he’s a really good baker who uses his state-of-the-art stand mixer to whip up delectable cakes, cookies and muffins. All gluten-free, by the way. It can be a real trick to make gluten-free baked goods that are out of this world, and Nicholas pulls it off on a regular basis.

Nicholas is a calm and comforting presence.

When the tumultuous circus of parenthood of howling toddlers and babies swirls around him like a cyclone, he takes it all in stride. He hugs the girls when they have a boo-boo and says everything will be all right, and it will be.

Nicholas is fair and reasonable, which comes in handy with family disputes.

I’ve witnessed one of his girls grab her sister’s doll, an act of war. He said to his errant daughter, in a gentle but firm voice, “That’s not nice. Would you want your sister to take your doll like that?” The doll was returned. Tears subsided.

Nicholas is loving and helpful.

He carries around a sleeping newborn strapped snugly to his chest while he’s doing dishes or picking up the house.

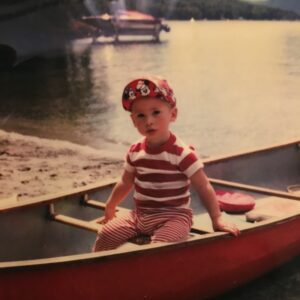

When I see Nicholas with his growing, beautiful family, I think back to when he was a boy, back to the times when I was the young dad.

I hope that I was a good one. I hope that everything I did along the way—being there for his lacrosse matches, hearing him sing at madrigal concerts, or turning couch cushions into castle walls—helped shape him into the great dad he is today. I’d be satisfied knowing I was half as good a dad as Nicholas is now.

Today, Nicholas inspires me to be a better grandfather.

So, here’s to the great dads. The bakers. The soothers of tears. The comforters. The huggers. The house-cleaners. The supportive husbands. The dads, like Nicholas, who bring their own brand of wonderful masculine energy to a world that badly needs it.

Hey Nicholas! Love ya!

Dad

PUBLISHERS NOTE: After I posted this story I received emails from readers who wanted to join me in celebrating the great dads in their lives. Here’s a story courtesy of Bob Abate, a reader—and grandpa—from New York. If you have a story to share, please post it as a comment here, or feel free to email me: ted (at symbol here) goodgrandpa.com.

A Father’s Day Remembrance

By Bob Abate

I believe my dad was the finest Man I ever knew. His birthday is a week after Father’s Day. Unfortunately, it will be a posthumous remembrance as he died in 1988. Yet, in many ways, he is more and more a part of my life with each succeeding year.

My dad was the oldest of five children and his childhood was shattered upon the sudden death of his father. At the tender age of twelve, he left school and worked whatever jobs possible. His motivation was quite simple – to help his mother, three younger sisters and brother survive. No work was too menial because nothing was more important than his family.

During the depths of the Great Depression, he found work virtually every day. In 1939, once his siblings had come of age, he married my mother and joined the New York City Fire Department—Washington Heights—once again, helping others. Several of my earliest childhood memories were learning that my dad had been injured in a fire and visiting him in the hospital. As a youngster, I thought that was just simply part of being a Fireman.

We shared a very special bond.

As the firstborn, I sensed his responsibility of raising four children and tried helping him whatever way I could. He often worked nights at the firehouse so his days would be free to do odd jobs. I would tag-along, helping him cleaning houses and washing windows after school or on weekends. He was talented with his hands and did fine woodworking and light carpentry to build furniture, toy chests, and woodworking projects for cash or barter. For years, our pediatrician check-ups and dental fillings were “paid-in-full” with bookshelves, personalized family photo albums and customized Christmas creches.

His philosophy of life was a simple yet universal truth – “It’s Nice to be Nice.”

As a teenager and young man, I thought that was simplistic and naive. As I’ve grown older and, hopefully somewhat wiser, I understand the wider implications of that elemental yet eloquent guidance. He practiced what he preached – his word was his bond. He taught by example all I ever needed to know about being a responsible adult, faithful husband, loving father and a doting grandfather. He was the hardest-working, most selfless man I’ve ever known.

Although not in the military, as a fireman, he faced his own special brand of hostile smoke and fire, almost daily, for three decades. My dad wasn’t very large – about 5 foot-7 inches and muscular – but to me, he was a giant of a Man – physically, spiritually and emotionally. I rarely recall not seeing him, just before going to bed, kneeling down and praying his rosary. Something else that the teenaged boy thought quaint but that the adult son cherishes as a symbol of the Faith of his Father.

Dad was unpretentious and quite dignified – proud and articulate.

His formal education stopped abruptly in the sixth grade yet his wisdom far-surpassed my degrees. He was always my biggest fan. My fondest memory is one hot summer evening, sitting on a park bench across from the Grand Concourse Hotel, near Yankee Stadium. I was twenty-one, just returned from the Navy and uncertain about my future. He assured me that any organization would be lucky to get me; if not, it would be their loss. I never forgot his comforting reassurance that night.

He was the finest man I ever knew and I mourn him more with each passing year. Time doesn’t necessarily heal every wound. At his funeral, I eulogized my Dad. I’m not one to show my emotions in public but there are times that just the mention of the word “Dad” triggers a flow of emotions that is unsettling but which I have come to accept.

He is constantly with me – in my heart and thoughts. I saw my dad three days before he suddenly died. He hugged me tightly, softly saying, “Bob, you’re a good son.” My fondest wish would be to hug him once again and tell him “You were a far, far better father; I love you, Dad.”