Peter Pan protested that he would not grow up. In the island of Neverland, he and Wendy could live a never-ending adventure filled with pirates, fairies and crocodiles, and they…

Peter Pan protested that he would not grow up. In the island of Neverland, he and Wendy could live a never-ending adventure filled with pirates, fairies and crocodiles, and they could fly.

As a grandfather, I’ve rediscovered my inner boy, that eternal Peter Pan that never really left me but was hidden from my vision for a while. I become Peter again when I’m building a cave out of couch cushions with my grandkids. Venomous snakes hunt across the jungle floor (the living room) in search of prey. A pterodactyl (me) swoops down and darkens the sky, talons reaching towards the mouth of the cave as the helpless little ones scream with laughter.

Childhood is indeed a magical place, but as parents and grandparents we know all too well that it doesn’t last forever.

When I was very little, I remember my dad would hold me up and rub my face against the stubble of his early morning beard, the sandpaper-like feel of it making me giggle. Then one day when I was older, he picked me up and was about to do what he’d always done, but I stopped him and said, “I don’t like that anymore.” He looked very sad. At the time I didn’t understand why.

But I do now.

As a grandpa, I’m experiencing time with a sense of increasing acceleration.

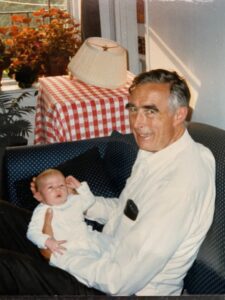

My eldest grandson is now 9, and the time between when I held that baby boy and the long-limbed seemingly pre-teen he is today, the one who is able to tackle me to the floor quite effectively, passed in the blink of a crocodile’s eye. And with this rapid passage of time I’ve become more aware than ever of the little changes I see in my grandkids, the moments I see them emerging from Neverland, sometimes in small steps, other times in giant leaps.

There’s great joy in seeing them progress upward in life (and all of them very tall, like me). Yet I feel an almost indescribable sadness when I see them leaving their own childhoods behind. A sadness that the magic I have witnessed—and rediscovered—is fleeting.

It’s one thing to experience this as a parent. As a grandpa, the emotions are all the more poignant because I know this is my last rodeo.

Each step that I see them take into adulthood has an air of personal finality for me because I know I will only see this once. And may not live long enough to see them have children of their own. This is it.

I recently had one of these joy/sadness moments on a Sunday morning. My son came over with his two girls to hang out and eat too many bagels, one of our favorite weekend activities.

Like most grandparents, my wife I read a lot to our grandkids. Whether it’s Goodnight Moon, or searching once again for the elusive rainbow elephant, we’re always reaching for another book. No matter what’s going on, or which grandchild is with us, we’ll ask if they’d like to read a book, and another, and another.

On this particular Sunday, I was in the living room with our youngest granddaughter, not yet 2 years old. She’s a very bright girl, cute and always fearlessly active (rock walls? Yes!) and highly focused on building Magna-Tile structures or whatever toy is before her. I was sitting in my leather chair, enjoying watching her bustle about. The sun was shining through multiple windows, filling the room with a bright, warm feeling. She was snapping Legos together, quietly figuring out what pieces would fit.

Then she looked up at me with her big brown eyes, picked up a book and held it toward me, and asked, “Would you like to read a book?”

I was startled. This very young girl, still in diapers and barely beyond infancy, had just formed a complete sentence, and the look on her face was suddenly so grown-up, so girl versus baby, that the joy/sadness of the moment struck me with full force. The part of me that was in the room then, fully present with my granddaughter, replied, “Yes, I would love to read a book.”

The other part of me, this boy inside who never, ever wanted to grow up, was flying with Wendy hand in hand through the night sky, the wind in my hair, heading home.

Second star to the right and straight on ’til morning.