Publisher’s Note: This lovely post was written by my daughter, Abigail Moore. As a grandfather, it’s wonderful for me to see that even though my father is no longer with us, his voracious mind is a legacy that continues through the generations.

When my parents broached the subject of organizing my paternal grandfather’s books I immediately volunteered for the task.

They were preparing for a long-anticipated flooring project, replacing the tired, stained, and occasionally smelly carpet in the primary bedroom. This sanctuary had previously been my grandfather Bill’s office, where he spent countless hours in his retirement puzzling over society’s ills and compulsively stocking his bookshelves with annotated and dog-eared volumes on a wide range of topics.

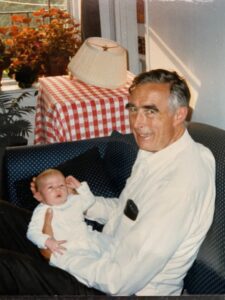

Grandpa Bill cut a formidable figure, running daily up and down the steep driveway of his house in the Northeast Kingdom in Vermont in a very small pair of shorts. This was the only time I ever saw him out of his customary button down shirt and belted khaki slacks, a formal uniform that he wore around the house, attending to his intellectual pursuits in his upstairs sanctuary.

All the grandchildren spoke in whispers about the day when they would come of age, and be summoned to meet with him in his office.

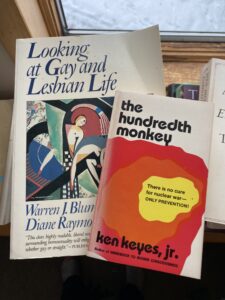

This ritual entailed discussing the evils of nuclear war, his time in the Navy during WWII, and his ongoing goal of ensuring world peace for future generations. My memory of my own conference centers around trying intently to avoid staring too hard at his eyebrows, which wriggled across his forehead like salt-and-pepper caterpillars, and general tween awkwardness and angst about having to discuss such a serious topic with my distinguished and somewhat aloof grandfather. Additionally, the graphic visuals of nuclear war were not for the faint of heart and needed to be approached with a certain degree of serious intellectualism.

In his twilight years, lost to the fog of dementia secondary to Parkinson’s, the office became an alarming representation of his mental decline.

Towering stacks of books covered every surface, some with hundreds of index cards protruding from pages inked with his favorite quotes and ideas. The room had an odor: unwashed clothes, faint traces of urine, and the musky scent of a neglected used bookstore or library. Piles of ladybug and house fly carcasses littered the windowsills and lazy skeins of cobwebs and dust fluttered in invisible breezes. I generally skirted the space, for fear of being drawn into a conversation in this claustrophobic and messy sanctuary that he refused to let anyone clean.

After his eventual passage from the mortal plain, his office and library remained as a concrete legacy of his obsessive quest for answers and information. When they took ownership of the house, my parents toiled for days to transform the space into a bedroom, but left the majority of his books on the expansive shelves. This was the library of a ghost whose presence continued to loom large over the years.

As a person who finds tremendous satisfaction in bringing order to chaos, likely as a coping mechanism for life-long anxiety, the prospect of systematically organizing the books was exciting to me.

We embarked on the project during the final days of February break, with everyone pitching in throughout a two-day sorting, purging, and cleaning extravaganza. Even my two boys, eight and six, dove into the task with uncharacteristic zeal. Brandishing dust rags and a vacuum they meticulously scrubbed and sorted with me for hours, occasionally finding treasures that they pored over together on the floor, heads touching.

The concrete result of this daunting and dirty experience was a bedroom filled with stacks upon stacks of hundreds of newly dusted books organized by subject.

However, a secondary consequence was a great deal of hilarity, discussion, and ultimately reflection about what these books represented about the passions and personality of someone long deceased. After immersing myself in the books for several hours, patterns emerged. Here was a person who had purchased, and hung on to, no less than five copies of On Death and Dying by Elizabeth Kubler Ross.

A preoccupation with long life, health, nutrition, self-diagnosis of illness, and stress was evident from a massive collection of books on these topics (medical texts on Urology: The Complete Series). Poetry, world-religions, encyclopedias, dictionaries, and classic works of fiction were predictable components of his library.

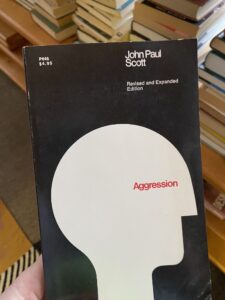

Non-fiction books about WWII and the devastation of nuclear warfare represented his time in the service, and his life-long guilt about his role in the Pacific Theater. A surprising number of tomes centered on gender, feminism, sexuality, and aggression in men (3 heavily dog-eared copies of Demonic Males by Dale Peterson and Richard Wrangham).

Here was a man who read The Joy of Sex (volumes 1 and 2) as well as Masters and Johnson (his one bookmark in the Joy of Sex Volume 2: How to avoid mischief makers in a threesome).

He appeared to be deeply interested in democracy, liberalism, and the emergent role of technology and its changing influence on society and culture. He was similarly passionate about evolution, anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

He had a comprehensive collection of works by B.F. Skinner and Maslow. His lifelong friendship with scientist E.O. Wilson was reflected in having multiple copies of his entire collection of published books. One of these featured my grandfather in the dedication, and further digging turned up the original proof of the book that Bill had annotated to share his comments/thoughts with the author himself. At times, I could not fathom how he could have slogged through countless ponderous tomes of economics, government, and comparative philosophy of leadership.

My grandmother, Janet, was evident in aged and crumbling pamphlets with knitting patterns, instructions for metallurgy, and gardening texts.

These were interspersed with books on other crafts that had a more direct impact on my childhood. I had vivid flashbacks to her teaching me how to make baskets one humid summer, and when she presented me with multicultural doll clothes for my American Girl doll (including a burka, which I mistakenly thought for many years was a very sophisticated beekeeping uniform).

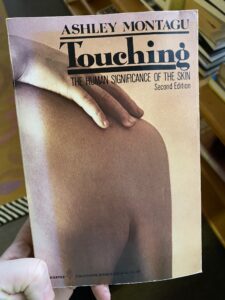

There were literary clues to other aspects of their relationship, revealing an unsurprising truth about his reliance on the written word to solve real world, interpersonal challenges (Touching: The Human Significance of the Skin by Ashley Montague; Choice Points: Essays on the Emotional Problems of Living with People, by John C. Glidewell).

Ultimately, I could not help but feel that I spent the better part of two days becoming reacquainted with someone who I had not seen in more than ten years (or twenty, if you consider the devastation of his dementia).

Flipping through the pages, and categorizing the collection, was a more intimate experience with my grandfather than I can recall having during his mortal life. As a person who loves books, and voraciously collects them and categorizes them in my own home, I wonder whether these will find permanence after my own death. In an increasingly digital world, there is a certain magic to a physical discovery of lost words, musings written in a margin, obscure and strange index cards tucked between dusty pages (“The leather coat was a strangler”). These forgotten and newly rediscovered remembrances made me laugh, sneeze, and ultimately wonder, “What the hell was Grandpa thinking?”