People will say that sickness is part of life, but the truth is that sickness has a life of its own. Sickness is a bubbling cauldron of living bacteria, a cornucopia spilling over with every manner of infection. Sickness is a field of blooming viruses, blood red and bobbing in the spring wind. These other forms of life, the uninvited guests that Poe described so horrifically in his Mask of the Red Death, are to us the ultimate party crashers, robbing us of the health and life we feel we are entitled to. And yet the bacteria and viruses are simply doing what all living things do, going about the business of thriving. They could easily protest that we are the ones crashing their party, when bodies give up and melt into the grass. We are, after all, literally the hosts of the party, and when our doors close they have no place to live either. So this battle goes on daily, and sometimes the toughest survive, or it has nothing to do with fortitude and everything to do with lucky genetic variations that make some immune enough to heal.

The calls and texts from Abigail crescendoed over a period of days. First, Henry had a cough. Then he had a bad cough. A really bad cough that was keeping him, Abigail and Ryan up all night. There was a worrisome rasping sound coming from Henry’s chest. A wheezing. A high fever that would not go away. They took him to the emergency room. Henry was admitted to the hospital and diagnosed with RSV – a lower respiratory infection. They put him on oxygen. Put in an IV. Henry, flat on his back and listless, would recoil in speechless horror when the nurses came to take blood or check his vital signs. If he were older than 17 months, he’d have full sentences to explain his terror – “Why is this happening to me?” “Who are these people who keep sticking me with needles?” But all he could say, or scream, was the word no over and over.

Nancy dropped everything and rushed to the hospital in Connecticut. I got a text from her that night that read, “Poor Henry is so sick.” Nancy is a very grounded person by nature, not prone to worry, but I could hear the deep concern in her voice when we talked that night. Most kids will get this particular sickness before the age of two. Henry’s case, however, was particularly severe. When the nightmare of the needle-fingered nurses relented to sleep, his oxygen levels dropped dangerously low, even with the oxygen tube taped to his face. We were sent pictures of Henry in his hospital bed, or sleeping on Abigail’s shoulder as she camped in a chair at three am under the florescent lights that can make even healthy people look ill. The bacteria in Henry’s chest was having a rager. A spring break. A ghoulish frat party. The more sickly the glow of the hospital lights, the brighter their revels.

It’s at these moments when you ask yourself something you can’t even think, and in conversations with your loved ones you can’t even say in words, so you speak around them with questions like, “How serious does the doctor say this is?” And the responses tend to trail off, the ellipses at the end of the sentence speaking volumes of dread, “Well, this happens to a lot of kids, and he’ll probably be fine, but…”

This question is inevitable and natural. It’s the one that’s on the surface that we ask in conversation with our spouse, our kids – the young parents toughing it out with our grandchild. It’s a question that goes deeper, though, much deeper, when we close our eyes and pray. I call myself a non-practicing Unitarian, which some would say is redundant. Churches and dogmatic teachings never meant much to me. But when your grandkid is sick, there is a God. And if there is a God when your grandkid is sick, then there must always be a God. I reached out to God and asked for help in healing Henry. I did point out, in my very reasoned Unitarian way, that I rarely asked for help from the Divine. So maybe this solitary plea might be heard, as if God had some kind of spreadsheet where she tallied the number or requests from mortals.

In my prayer, I pictured Henry in his hospital bed, sleeping. I was there, above the whole scene, creating a loving embrace that could let Henry know that he was not alone in his fight to turn off the stereo at the all night bacteria party. It was time for the partiers to go home. This place was no longer for them. They could continue their party someplace else, but this party was over.

I am convinced, through repeated experiences, that there is in fact a force of some kind that connects all of us, and it connects our families to an even greater extent, no matter where we are on Earth. Underscoring this connection is a river that holds all knowledge and awareness, a river that runs unseen beneath our conscious reality. All of the answers are there. When we listen to it (very intently, shutting off the noise) we know what we need to know. This river doesn’t use a lot of words, only the most important ones. That night, when I prayed for Henry – when I listened for Henry – I heard that he was going to be all right.

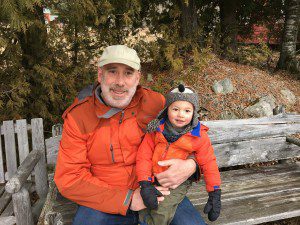

Three months later, I walked down to the beach on Lake Willoughby with Henry, Abigail and Ryan. It was a cool early April day, the sky mostly cloudy. Half the lake was still covered in ice. The grass along the shore was still brown. Henry ran around happily in his bright orange coat, picking up sticks – “Sticks!” and laughing as Abigail’s dog, Rory, leapt into the freezing gray waves.