In November of 2021 I started experiencing sharp pains on the right side of my groin, a feeling of being stabbed by an invisible force.

My doctor ordered up a series of scans to “rule out anything bad,” as he put it. When the ultrasound and CAT scan results came back the doctor reported there were no signs of anything that would cause the pain. And yet it kept getting worse. I’ve always turned to swimming and yoga to get through physical issues, but after 20 minutes swimming laps, or a yoga session, I was in so much pain I was literally curled up in a fetal position on the floor, in tears.

I went back to my doctor. “Something’s really wrong,” I said.

He replied that the medical world doesn’t really understand pain. To get me through the agony, he prescribed a drug called gabapentin, a neural pain blocker that doesn’t totally remove pain, but dulls it. I found it also dulled my sense of reality, sending me into a moody dark blue underworld nightmare of drowsiness and depression. That plus opioid painkillers was turning me into a zombie. I started lying in bed a lot more (the only time I wasn’t in as much pain), or taking very long hot baths.

This went on for about four months. Increasingly desperate, I began checking out resources for chronic pain management, including a residential clinic in Florida run by a leading hospital system. I’d have to go and stay in a facility for a month, taking classes in meditation which, combined with drugs, could help me at least survive without going out of my mind.

All of this was also very hard on my wife. She was deeply worried about my trajectory, and at one point asked what she would do if I died.

But she kept seeking answers and never stopped asking questions. “Is it possible,” she asked one day, “that the pain has something to do with the hernia surgeries you’ve had?”

I put this question to my doctor, who suggested I reach out to the surgeon who had done two hernia repairs on me over the past two years. Three weeks later I was in the surgeon’s office. This was in April of 2022. He took one look at the CAT scan done in December of 2021 (the one my doctor told me was totally fine) and said, to my complete astonishment, “You have a hernia in your groin, on the right side. An inguinal hernia.”

I exclaimed, “Are you fucking kidding me?”

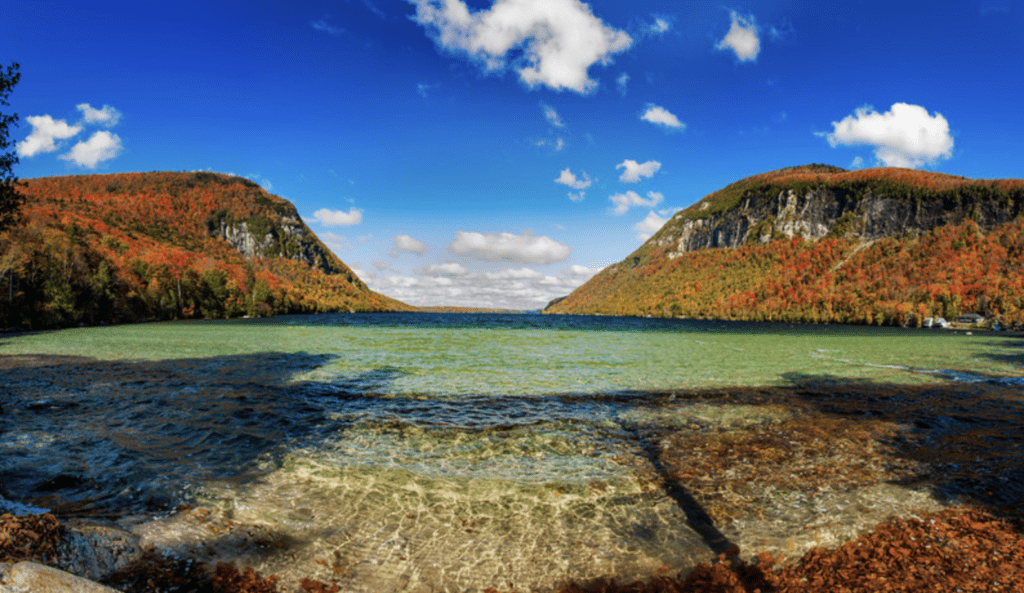

I had the hernia repaired in the middle of May, just prior to coming back to our place in Northern Vermont near the shores of Lake Willoughby.

The lake is in the heart of a corner of Vermont called the Northeast Kingdom, a name coined by Governor George D. Aiken in 1949. The name stuck, although many people in these parts have shortened it to “the Kingdom.” One might wonder who the king is. The answer is anybody and everybody, from the Amish who sell amazing baked goods on Saturdays, to the guys who work at the dump, to the woman who runs the Museum of Everyday Life, to the workers at the Pick & Shovel – a hardware store with the tagline, “If we don’t have it, you don’t need it.”

At the South end of the lake are two mountains, Pisgah and Hor, which used to be one before a glacier long ago cleaved them in two. Today, the mountains face each other on opposite sides of the water with steep rock cliffs, like an old couple on their country porch with nothing more to say.

The glacier may be gone, but the cold remains.

The locals say that July and August are just two months of bad sledding, and they’re only half kidding. It’s not uncommon to get howling snowstorms in late May or September. The lake, fed by innumerable mountain streams, never really gets to a temperature most people would call warm. It’s usually just plain cold, a deep five-mile-long expanse of frigid blue water that’s eyed warily by paddleboarders carefully calibrating their balance.

And so, with post-surgical bandages still stuck to my abdomen, I found myself on the shores of the lake on a frosty raw day in May. I waded slowly into the 47-degree water, with each inch of water bringing numbness to my feet and legs as I walked in deeper, coming to a stop after the water was just above where the hernia had been repaired.

In an instant all discomfort was cooled—or frozen—into submission. It was blissful.

I stared out at the green mountains and the dark lake all around me. I felt the cold wind on my skin. I said to myself, I’m going to be ok. I’m going to be great, actually. I’m going to return to swimming and become strong and healthy again, bit by bit. I’m going to be there for my four grandchildren.

I returned to the lake each day to submerge myself as far as possible into the freezing waters. It was a brief yet total respite from all discomfort, and with each passing week I went a little deeper, a little farther.

Once I got the go-ahead from the surgeon to fully immerse myself in the water, I started swimming. This was early June, with water temperatures still in the low 50s. The water and air were so cold that I’d get some level of hypothermia every time I ventured out, with shivering that only subsided after a mug of hot tea consumed next to a roaring fire. I found, though, that there is a switch in my mind that I can flip to ignore the cold, and embrace it at the same time. The first step is to acknowledge that it’s there. The next step is simply to dive in and go as fast as possible, surging ahead through an early morning flat calm or tempestuous afternoon waves.

Being aware of the cold and fully present in the moment opened up a vista of sight and feeling I had not experienced before.

When swimming underwater during heavy rain, for example, the pelting droplets hitting the water’s surface above resemble a scintillating meteor shower. It’s breathtaking.

By the end of June I was swimming about a half mile each day. The sharp pain I’d been experiencing before the surgery had vanished. The surgical site had healed completely. Just as important, my mind was starting to heal. I couldn’t tell how much of my improved mental state was due to the anti-anxiety medication, or if it was due to the absence of pain. Or maybe just being in the water again, moving, surrounded by lake and sky and mountains was bringing me home to myself, the normalcy I had so long wished for.

Along the path of my return journey to wellness I’ve had companions. They are called Loons, common to this part of New England in the summer months.

Loons look a lot like ducks, but they are different. For starters, loons are very good at diving deep to catch fish. When I’m swimming along, one eye under water and the other above, I’ll spot a loon pop up to the surface, or dive down. Unlike most wildlife, they seem completely unconcerned with being close to people. Sometimes they’ll fish within a few feet of me, almost as if they’re joining me for my daily exercise.

The most distinctive thing about loons is their sound. Ducks quack. Eagles screek. Birds chirp. But loons make a long, sonorous aria that rises and falls like a wave; it’s haunting and lovely. Living near the lake means always hearing the loons. Late at night in those periods of wakefulness at 3 am the loons can be heard, often several at once. When I’m swimming their music is closer and more intimate.

In my family, we joke about who our spirit animal is. I’ve always said mine was a groundhog, probably because I’ve had to rid my basement of them several times. They want to live in my house as much as I do.

It’s the loon, though, that may actually be my sprit animal.

We have this lake in common, this amazingly beautiful lake. We return to it again and again for our nourishment and health. The cold does not faze us; in fact, it’s part of the lure that pulls us in as we splash and dive. And, of course, we both sing on a regular basis.

Today, I am strong and healthy as September arrives and the cold air returns. The nightmare I experienced is in the past. And yet I know it’s inevitable that some other health problem will occur in time. That’s ok. Now I know where I can go to heal, and who will swim alongside me.