It was Easter, 1969, a lovely spring day in Lexington, Massachusetts, when my family—mom and dad and my four older brothers, loaded into the station wagon and headed over to my grandparents’ house across town for the traditional late afternoon feast of ham, potatoes, peas pies and handfuls of chocolate easter eggs.

I was 10 at the time, while my oldest brother, Calvin, was twenty-one, and Charlie, nineteen. Both draft age for Vietnam. The war seemed far away. Photos taken that day seem inked in pastel hues, all of us in jackets and ties, young and pink-faced.

But the war was not far away, not really. Every night we watched Walter Cronkite on the evening news, and there was always a tally of the men who had died in Vietnam, and often war footage from the dreaded jungles and rice paddies. My parents were very much against the war and were not shy about saying so. Dad of course was no stranger to war, having been divebombed by kamikazes at the battle of Okinawa. He often said war was the stupidest thing he’d ever seen, and Vietnam only confirmed his beliefs. He did his part to serve his country, suffered life-long trauma he did a reasonable job of hiding from the rest of the world, and carried on.

Calvin and Charlie were nervous about the draft; there was a lot of nail biting going on, literally.

Calvin was still a bit on the fence, though, about whether he’d go to Vietnam if his draft number came up. He’d been in ROTC in college and was better prepared than most of his peers to fight. But he also paid close attention to the news and the more he heard the more he believed Vietnam was not winnable, and hence not worth dying for.

And nobody in our family liked Richard Nixon. Mom, who never swore, once shouted at Nixon’s face on the TV, “You’re just a bucket of shit!”

My grandparents, Fred (Gramp) and Harriet (Gram) did however approve of Nixon.

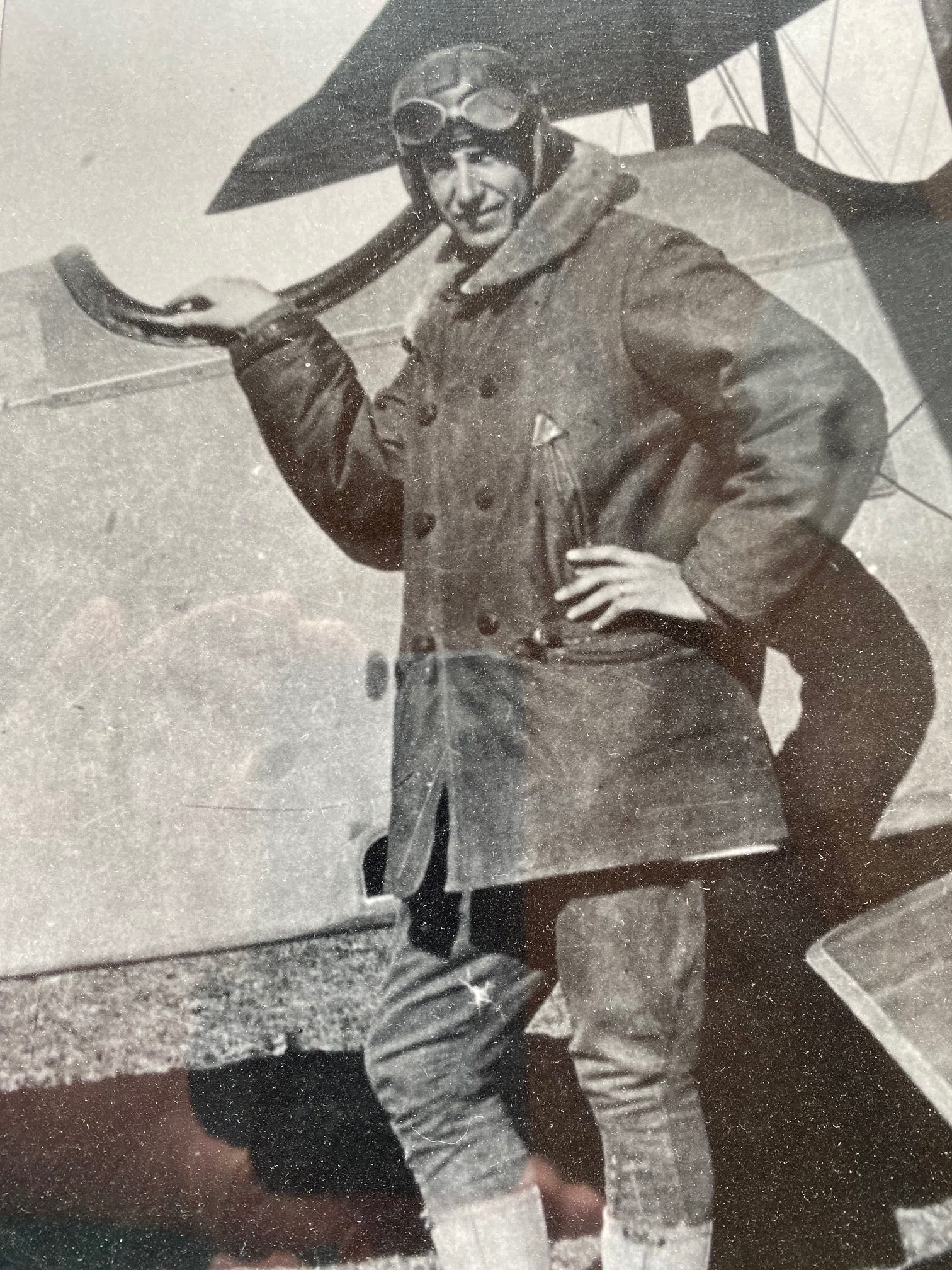

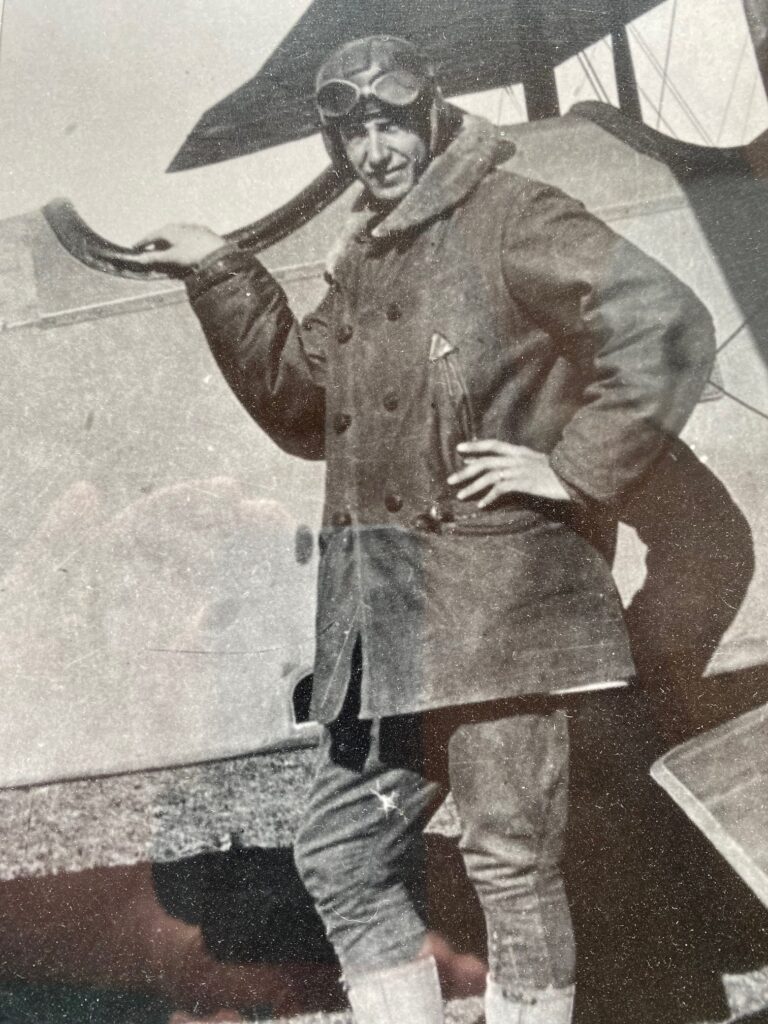

They were Republicans through and through. Even if Nixon had his flaws they would always support the Grand Old Party. Gramp, well into his 70s on that Easter day, had flown a biplane in WWI to help photograph the trenches for intelligence. In WWII he returned to service and rose to the rank of Colonel in the air force. Gramp was six foot three, with an aquiline nose, piercing eyes, and a generally commanding presence. When I worked for him as a teenager to help with chores at his summer rental cottages on the shores of Lake Willoughby in Vermont, he didn’t ask me to do things; I knew they were orders and saying no was not an option.

After we’d gorged ourselves on Gram’s multi-course dinner, we retired to the living room. Somehow the topic of Vietnam came up.

My grandparents never said a word about Vietnam, which is why what Gramp said that day was so astonishing.

While my older, draft-aged brothers and I listened on, Gramp said. “Well, boys, when I went to war the first time, in World War I, they told us it was the war to end all wars. Then came World War II don’t you know, and we had to go back and fight another one. Then there was Korea. And now there’s Vietnam.”

Here he gestured one long hand in the air for emphasis and fixed us with his piercing eyes, “All I can tell you is, it’s always the old men who start wars, and it’s the young men who are sent off to fight them.”

None of us said anything in response, but heads nodded. We knew exactly what Gramp’s opinion of Vietnam was, without him ever having to be explicit or betray his Republican principles.

With war now once again raging in Europe I’m reminded of the truth that Gramp told us that day. Unfortunately, it’s the old men who are in power—one evil old man in particular—and the young men believe they have no choice.