It was an early morning in July 1918, cloudy with a strong wind blowing as the American pilot flew his Nieuport 28 biplane over Chamery, a hamlet of Coulonges-en-Tardenois not…

It was an early morning in July 1918, cloudy with a strong wind blowing as the American pilot flew his Nieuport 28 biplane over Chamery, a hamlet of Coulonges-en-Tardenois not far from the front lines. His mission: Scout out and shoot down German reconnaissance. The fields of France were lush and green below, expanding out to the horizon where a glimmer of sun shone through the clouds, with dark trenches coiled through the fields like venomous snakes.

The roar of the planes behind him was his first sign of trouble.

He turned with alarm to see three Fokker Chasse planes bearing down on him from above. He yanked the stick hard to maneuver and climb into a more favorable fighting position, hearing the rattling bursts of machine gun fire growing nearer. It was too late. Within seconds, he was shot twice in the back of the head. His plane turned over on its back and plunged to Earth.

Back home on Long Island, the young man’s father—former President Theodore Roosevelt—mourned deeply from afar. Roosevelt put on a brave face for the press, but many believed he was so heartbroken he never recovered, and died barely a year after his favorite son, Quentin.

In the same French skies that year was another American pilot, Lieutenant Frederick L. Fish. The son of a Vermont State Supreme Court justice, Fred was tall, with short-cut sandy brown hair, a long face with an aquiline nose and clear grey-blue eyes. As he flew, Fred looked down at the battle below, a muddy moonscape of devastation, trenches separated by undulating piles and pits from shell blasts, shattered tree trunks pointing at twisted angles.

Fred pulled the trigger. But instead of firing a machine gun, he was snapping the shutter of a camera mounted to his plane, photographing enemy positions to provide intelligence to army headquarters. Fred was smart. Resourceful. Brave. Lucky as hell.

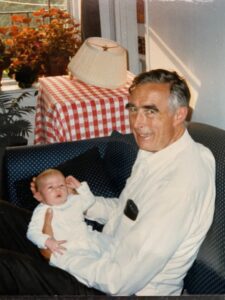

Fred was also my grandfather.

After the war, Fred Fish became a successful salesman, and in middle age became a Colonel in the Air Force in WWII to help organize allied resources for the D-Day landings.

I got to know Gramp very well, thankfully, when I was a teenager working for him to help manage and clean his rental cottages on our family farm along the shores of Lake Willoughby in Vermont’s remote Northeast Kingdom. The five-mile-long lake was formed when a glacier bore down from the North, cutting a deep trough in the land and splitting one big mountain in two—Mt. Pisgah and Mt. Hor—with steep rock cliffs that slope down to the deep lake waters. The family’s rental cottages, all painted red with white trim, lined a sandy beach and hugged the banks of a brook that flowed from Westmore mountain.

Even then, in the 1970s, Gramp had a commanding presence.

Though bent with age, he was still tall at six foot two, and was quite comfortable giving orders and seeing that they were obeyed without question. He was usually dressed head to toe in khaki, including a cap, and would fix me with his clear eyes and tell me to do this (empty buckets of sewage out of a septic well) or that (rake the beach). Or the Sisyphean task of cleaning the cottages in-between rentals using an upright vacuum that had terrible suction. “You missed a spot!”

I can picture him now vividly as he kicked back at the end of a long day, drinking a Miller High Life in the yard behind the Farmhouse. “Teddy,” he’d say, “there’s no substitute for hard work.”

Gramp lived into his mid-eighties, always active and full of life. He sang hymns in Church, delighting everyone with his vibrant baritone voice. Often down at the beach he’d break into yet another chorus of his favorite song, The Foggy Foggy Dew.

Why does the fact that Gramp survived two wars and lived a long life matter? Why did it matter to him, and—for the purposes of this story—why did it matter to me, my brothers and cousins? Just as important, why did his very nature as a grandfather matter to us, complete with his many tales of adventure and shared wisdom?

It turns out it matters a lot. Not just in the case of my Gramp, but for all grandpas and our loved ones here in America and around the world. The reasons are rooted in the history of humanity itself.

Early humans lived lives that Thomas Hobbes best described as “Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Fossil records indicate that our very earliest ancestors 30,000 years ago lived to about the age of 30. Which meant very few lived long enough to become grandparents. Scientists aren’t sure why Upper Paleolithic Europeans started to live longer into relatively old age, but they surmise that the changes brought about by this longevity had a profound impact on evolution.

When more grandparents came on the scene, things started to change for the better.

“Grandparents,” an article in Scientific American informs us, “contribute economic and social resources to their descendants, increasing both the number of offspring their children can have and the survivorship of their grandchildren.” In other words, having grandpa and grandma hanging out in the cave meant they were there to help raise the kids and dole out essential knowledge. Grandparents could teach, from experience, how to plant seeds to get the best crops. Or a thousand other things that helped the family survive and thrive.

Gramp’s habit of telling stories ladled with wisdom is likely a key reason why several of my four older brothers survived into adulthood.

Here’s one story out of many that shows how Gramp made a difference.

It was Easter, 1969, a lovely spring day in Lexington, Massachusetts, when my family—mom, dad and brothers—loaded into the station wagon and headed over to my grandparents’ house across town for the traditional late afternoon feast of ham, potatoes, peas, pies and handfuls of chocolate Easter eggs.

I was 10 at the time, while my eldest brother, Calvin, was twenty-one, and Charlie, nineteen. Both draft age for Vietnam. Photos taken that day seem inked in pastel hues, all of us in jackets and ties, young and pink-faced.

The war was not far away. Every night we watched Walter Cronkite on the evening news and there was always a tally of the men who had died in Vietnam. My parents were very much against the war and were not shy about saying so. Dad was no stranger to war, having been divebombed by kamikazes at the battle of Okinawa. He often said war was the stupidest thing he’d ever seen, and Vietnam only confirmed his beliefs. He did his part to serve his country but suffered lifelong PTSD. I once witnessed my mom give him food in a red dish, and when he saw the color red he clenched his teeth and screamed, “Blood!”

Having seen dad’s post-war stress up close, Calvin and Charlie were nervous about the draft; there was a lot of nail biting going on.

Calvin was still a bit on the fence, though, about whether he’d go to Vietnam if his draft number came up. He’d been in ROTC and was better prepared than most of his peers to fight. Both my parents hated Richard Nixon. My Gramp and Gram, however, were lifelong Republicans through and through. Even if Nixon wasn’t perfect, they would always support whoever led the Grand Old Party.

After we’d gorged ourselves on Gram’s multi-course dinner, we retired to the living room. Somehow the topic of Vietnam came up. My grandparents never said a word about Vietnam, which is why what Gramp said that day was so astonishing.

Gramp held court in his chair, center stage, while we young men sat nearby in respectful silence. “Well, boys,” Gramp said, “when I went to war the first time, in World War I, they told us it was the war to end all wars. Then came World War II don’t you know, and we had to go back and fight another one. Then there was Korea. And now there’s Vietnam.”

Here Gramp gestured one long hand in the air for emphasis, “All I can tell you is, it’s always the old men who start wars, and it’s the young men who are sent off to fight them.”

None of us said a word in response, but heads nodded. We knew exactly what Gramp’s opinion of Vietnam was without him ever having to be explicit or betray his Republican principles. None of my brothers chose to fight in Vietnam.

Only a man who’d flown above the trenches in France, then returned to Europe to fight again not too long after, and only a man who loved his grandsons more than anything, had the moral credence, love and wisdom required to tell us what he did. My brothers and I lived on to have children and grandchildren of our own.

What are lessons that I and other grandparents can impart to help nourish the next great generation? What role does wisdom play in survival and happiness?

In future posts, I’ll offer up some ideas. Not only mine, but gems of wisdom I’ve heard from other grandparents. If you have suggestions or would like to write a guest post, drop me a line at teddypage@gmail.com.