In the early hours of May 1, 2023, a single engine Cessna 206 crashed like a meteor into a remote jungle of the Columbian Amazon.

The plane carrying the family crashed in a part of the Amazon that had never been explored.

On board was a mother and her four children, aged 13, nine, four and one; the pilot and one other adult died instantly, the mother likely lived just long enough to warn her kids to get out. The children crawled through the wreckage into a part of the Amazon that had not yet been explored, a place so wild it could have been a different planet. They were in “a very dark, very dense jungle,” explained indigenous expert Alex Rufino, “where the largest trees in the region are.” News reports of the crash described the area as .”(1) This description dramatically understates the extent of the danger these children faced, alone.

Take the snakes, for example. The amazon is home to the Anaconda, a behemoth that can weigh up to 500 pounds and grow to 29 feet long. It wraps around its prey then swallows it whole. Then there’s the Bushmaster snake, which is only about 12 feet long but is incredibly poisonous and capable of multi-bite strikes, followed by the Amazonian Palm Viper, the Fer-De-Lance, and last but not least the South American Rattlesnake.

If by chance the children were not poisoned by snakes, they’d have to contend with the Black Caiman alligator, one of the largest predators in the Amazon basin. It can grow to be over 16 feet long.

The kids could also come into contact with a Poison Dart Frog, which has a skin so toxic that merely touching it can cause paralysis and death.

More unpleasantries awaited if the children went into a body of water, which in the Amazon can be inhabited by sharp-toothed Piranhas, and Electric Eels—a fish that can send out a 600-volt shock powerful enough to incapacitate an adult. Then of course there is the Potamotrygon Stingray, the Bull Shark and the dreaded Candiru — known as the Vampire Fish due its ability to lodge in its victim’s genital track where it feeds on blood.

The insect world delivers its own house of horrors: Bullet ants, Brazilian Wandering Spiders, venomous fanged 10-inch-long Amazonian Giant Centipedes, the Tityus Scorpion and the Goliath Birdeater — at about 12 inches it’s the largest spider in the world.

The Brazilian Wandering Spider

If the hungry children ate the fruit of the Strychonos Plant, which resembles clementines, they would ingest a juice used for making poisonous arrows.

But why worry about treacherous snakes, insects, fish and fauna when there are Jaguars nearby, a predator that can reach speeds of 50 miles per hour?

If you followed news of the crash, you may already know that 40 days later the children were found alive. There are many heroes who can take credit for their miraculous survival, but the one who caught my attention was the children’s grandmother, María Fátima Valencia, who raised them from a young age and taught them the ways of the jungle. Members of the indigenous Huitoto people, they knew to avoid the poisonous fruit of the Strychonos Plant and instead hunt for the Avichure tree—known as the milk tree—and chew its sugar-rich seeds, or the oily fruit of the Bacabapalm. They knew how to get drinking water while avoiding Piranhas. And do their best to hide from lurking Jaguars.

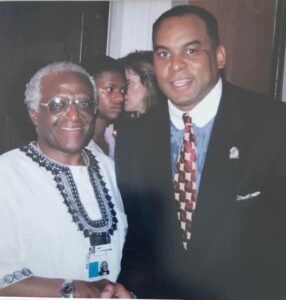

When military helicopter crews hunted for the children, flying low over the thick green jungle canopy, they broadcast a message recorded by María: “I’m your grandmother! I ask you a favor: You need to keep still because they are looking for you, the army!” If there was a prize for 2023’s Badass Grandma of the Year, María would have won it hands down.

Here in the United States, we don’t have an Amazon jungle, but we do have Amazon — the most efficient way to buy and receive boatloads of crap the world has ever seen.

I don’t mean to pick on the good folks at Amazon here (I’m a customer and a stockholder, and appreciate the cat litter they delivered last week, same day no less). I’m simply using Amazon to illustrate the world of modern products that pose as improvements, yet hidden within them are dangers as venomous to our grandchildren as Yellow-Bearded Vipers. When I speak to grandpas about what they fear most when they think about our grandkids’ future, the top bogy man is technology. Internet media, kids’ faces glued to screens, and the rise of artificial intelligence are the new jungle, and there is no indigenous guide to teach survival skills.

If we journey into our Amazon, here’s just a few examples of the pestiferous things families can order today.

For $264.99 we can buy a Galaxy A25 5G A Series Smart Phone with 128GM, an AMOLED Display, Advanced Triple Camera System, Expandable Storage and Stereo speakers. Forty-two percent of U.S. children have a phone like this at the age of 10. By age 14 that number jumps to over 90 percent.(2) This is not surprising given that children beg their parents for smart phones as if they were candy. The phones themselves may not be yummy, but what kids consume with them certainly is. Watching internet media releases dopamine into the brain’s pleasure centers—the same chemical released by eating delicious food or snorting cocaine.(3) And the more our grandkids eat up this media, the worse off they are. Scientists have found that there is correlation between how much time kids spend on social media and how depressed they are.(4)

In addition, there’s evidence from a UCLA study that shows that the increased use of smart phones and the resulting lesser time spent for face-to-face interaction leads to the decline in social skills among kids.(5)

If Smart Phones were alcohol or some other drug they’d be illegal for minors. Yet parents often give their kids smart phones to make them happy, or to mark a passage into adulthood like a Middle School graduation present, without fully understanding the creatures hidden inside complex circuits and Internet algorithms. Imagine a parent from the Huitoto indigenous community giving their kid a Tityus Scorpion, only worse. At least the scorpion is self-evidently dangerous so the kid wouldn’t try to play with it. But kids interact with their smart phones all the time without any hint of danger. The average teenager spends nine hours a day looking at screens.(6) Young kids have less screen time but may be at higher risk. Toddlers who spend more than two hours a day in front of screens have an increased chance of delayed speech development.(7)

Search Amazon for laptop computers and you’ll get an amazing deal on the 2024 Chromebook for students and businesses ($299 with one day Prime delivery). What parent wouldn’t want their young scholar to have the very best technology in hand when they go off to college Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work that way.

Just like phones, laptops and the media they serve up can be incredibly distracting.

Students type notes in lectures on their laptops or do their homework, but frequently jump away to check the latest Facebook/X/Instagram/Tik-Tok postings, which totally messes with their mental focus. Teens may claim they are good at multitasking, but scientists have demonstrated that people in general are simply not hardwired for it.(8) It takes about 20 minutes after being interrupted before mental focus is regained.(9) A study conducted at Harvard University found that just being near another student who is multitasking on a laptop during class results in poorer grades.(10)

Setting aside the hazards of media and distraction, excessive amounts of screen time is bad for eye health.

Most digital screens emit high amounts of blue light, creating what scientists refer to as the Blue Light Hazard (BLH), which can harm the retinal cells in the eye.(11) Children’s eyes are still developing, making them likely more susceptible to retinal damage from blue light. More than 65 percent of blue light is transmitted to the retinas of young children. At age 25, those numbers change to between 20 and 50 percent, depending on the specific wavelength of the light.(12) New types of non-emissive screens made with E Ink ePaper provide a much healthier screen time alternative, but few people are aware of it.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a whole different beast.

I’d read about all the buzz and decided to try it out, enlisting the help of Google’s Gemini to write a blog post about being a grandfather. Technically, Gemini is a conversational generative artificial intelligence chatbot. But Google calls it, “Your creative and helpful collaborator to supercharge your imagination, boost productivity, and bring ideas to life.” Based on what it wrote for me, I’d agree it supercharges my imagination, although not in the way Google may have intended. I was astonished that Gemini did reasonably well, instantly crafting sentences such as…

“Being a Grandfather: The Best Job in the World.

Being a grandfather is one of the most rewarding experiences in life. It’s a chance to relive your own childhood through the eyes of your grandchildren, and to pass on your love, wisdom, and experience to the next generation.”

The more I read, the more it became clearer to me that Gemini’s AI algorithm was pulling ideas from my own Good Grandpa blog. All AI programs are designed to do this. What they “write” is not original per se, but rather in instant conglomeration of the most relevant stuff on the Internet. The following sentence from Gemini is basically digital plagiarism — not a word-for-word rip-off but pretty damn close:

“Being a grandfather is more than just fun. It’s also a great responsibility. You have the opportunity to make a real difference in your grandchildren’s lives. You can help them to learn and grow, and to become the best people they can be.”

In 1950, a British cybernetics pioneer named Alan Turing developed what he called The Imitation Game, known today as the Turing Test. The test was designed to determine a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, we humans. The Turing Test is more relevant today than ever as AI chatbots proliferate. How can we tell if an AI program is writing or speaking, or if it’s a real person?

For my Good Grandpa blog post, Gemini failed the Turing Test in glaring and hilarious fashion with this sentence: “If you’re thinking about becoming a grandfather, I encourage you to go for it.”

From Gemini’s perspective, we have total control over when we’re going to become grandparents, like it’s deciding if we’re going to join a gym or taking up knitting. Running with this idea, here’s an imaginary father/daughter conversation.

A phone rings. A young lady answers.

“Hi dad!”

“Hi, honey, how are you and Peter doing?”

“Good, good. Busy. How are you and mom?”

“We’re great. Planning a trip to Albuquerque in the spring.”

“Nice.”

“Oh, and one other thing. I’ve decided to become a grandfather!”

Pause. Silence.

“I see, well, that would be wonderful, someday.”

“I’m thinking now, actually.”

“But Peter and I aren’t ready to have children! We’re going to do some traveling first and…”

“Sweetie, you’ve been married for five years and it’s time to start procreating. Mom and I aren’t getting any younger.”

It’s a sure thing that AI capabilities will rapidly improve, but based on its automatic notions of total control I can only hope that future iterations will never be given access to the nuclear launch codes.

I would be remiss if I didn’t give a shout out to my least favorite modern technology of all, now available on Amazon with free delivery right to your yard — the leaf blower (such as the Husqvarna’s 125B Gas-Powered Leaf blower for only $196.00!). If products could go to hell, there’d be a special circle in the inferno for these deeply annoying machines. Quiet fall days are a thing of the past. More often than not there are multiple leaf blowers whining incessantly like an off-key monotonous chorus of monks. Many people will say that leaf blowers are a necessary evil. But if we add up enough small but necessary evils, it amounts to an incalculable loss for our grandchildren.

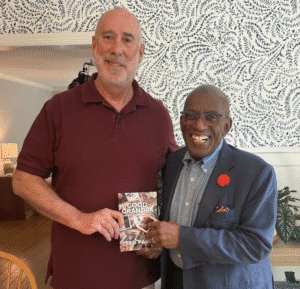

Here’s my point. We grandparents grew up in an analog world and it’s up to us to let our children and grandchildren know that new technology isn’t a de facto improvement, and often it represents a giant leap backwards. A few years ago, I was touring an exhibit on industrial design at a museum in New York City when I came upon the same stereo turntable I had in college in 1978 (this was the moment I realized that I myself was an antique, but hopefully one that could still make beautiful music). Lots of people still prefer the warm sonic depth of vinyl records over the digitally cold Spotify vibe. Instagram has filters that let you make your pictures look like Polaroids from 1970. I worked for Polaroid and I can assure you that my SX-70 took way better pictures—with richer and more painterly hues—plus the picture popped out of the front of the camera so you could save it in an album or stick it on the fridge.

Most pictures taken with smart phones ultimately get lost in a digital ephemera, including those of our grandkids; shouldn’t we hold on to the pictures just as tightly as we hold them?

Today, as technology advances with growing speed, I don’t think we should fear it. To quote Frank Herbert’s classic Dune science fiction series, “Fear is the mind killer.” We simply have to get educated on technology’s hidden dangers in order to protect and nurture those we love. If we’re going to help our grandchildren become the greatest generation, we need to be the voices of experience and wisdom broadcast from the helicopter flying over our Amazon —

“We’re your grandparents! We ask you a favor: Turn off your smart phone! Close your laptop! Be social with your friends face-to-face instead of on Facebook! Stay focused on your homework so you can gain Actual Intelligence (AI) instead of the artificial kind! We love you! Now, grab a rake!”

Sources:

- BBC

- Forbes Health

- The Guardian

- Child Mind Institute

- The Healthsite.com

- Common Sense Media

- Pediatric Academic Societies

- Mayer and Moreno

- Society for Human Resources Management (SHRM).

- Technology and Student Distraction, Harvard University Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning.

- Blue Light Phototoxicity Toward Human Corneal and Conjunctival Epithelial Cells in Basil and Hyperosmolar Conditions, Marek V., et al. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 126:27-40.

- Light-emitting diodes (LED) for domestic lighting: Any risks for the eye? F. Behar-Cohen, C. Martinsons, et al., Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2011.