Once upon a time in a land far away and long ago, my dad used to make up stories for us at bedtime.

All his stories involved the same seven characters, Casper, Jasper, and five boys named Calvin, Charlie, Nick, John and Ted — me and my four older brothers. I recall loving the stories, but that’s all I remember because they were never written down.

When my two kids where little, I took a page from my dad’s dreamtime creative playbook and made up my own stories to tell them at bedtime. My kids remember loving the stories, but that’s all they remember because I never wrote them down.

These days, coming up with stories that feature my grandkids is as wonderful for me as it is for them, and maybe I’ve finally learned my lesson because I’ve started writing them down so they’ll never be lost.

My grandkids jump into bed and implore me, “Grandpa, tell us a story!”

Then—like the grandpa in The Princess Bride—I spin a tale of magical adventures. I’ll often pause in the middle of a story to offer up different branching pathways and give the grandkids a choice of which way to go, or ask them to create and vote on the best solution for beating the dragon, crossing the fiery swamp or outwitting the ogre.

Of course, it’s inevitable that they get so excited that going to sleep is impossible. I completely fail at the ‘get the kids calmed down’ concept and I’ve taken some heat for it. I beg forgiveness. Many years from now, my grandkids will never remember that they lost a few hours of sleep, but they will remember the stories I told them and the special time we had together.

These are Forever Stories, cut from the same cloth as Forever Letters but with a creative twist.

Here’s a recent tale:

Lucinda had been playing with her Teddy Bears—Henry, Charlie, Roen and Mae—for much of the afternoon on a green spring day in the little town of Oakdale, Connecticut, when she yawned very wide and said, “Oh goodness. It must be nap time.”

Lucinda’s mom, Fern, called up from downstairs just at that moment, “Lucinda! Time for your nap!”

Lucinda gave her bears a big hug and a kiss, and set them down side by side in the playroom. “Sleep tight, my fair princes,” she said. Lucinda’s mom tucked her into bed and soon the little girl fell into a deep sleep.

But in the playroom, things were just starting to wake up.

In the dimness, a small red light blinked on and a man’s voice crackled over a radio. “Calling all Teddy Bear Rescue Squads. Calling all Teddy Bear Rescue Squads. Can you read me?”

The Bears jumped to their feet and ran to the radio. Charlie pressed the red button and whispered, “Squad one reporting! I repeat, squad one reporting! Over.”

“Roger that, squad one!” said the voice. “We need you down at the playground immediately! A tiger has gotten loose from the zoo, and if he’s not put back in his cage who knows what could happen!”

“No problem!” said Henry. “We’re on it, Chief!”

“Let’s go!” piped up Roen, a girl bear.

“Let’s go!” chimed in Mae, Roen’s little sister, who was learning how to talk and often repeated whatever her sister said.

The bears had a quick meeting, trying to keep their Teddy Bear voices down. In case you’ve never heard a Teddy Bear talk, it’s a very high pitch, almost like hearing a baby ask for crackers or something. Use your imagination.

The question now was, should they take the Rescue Squad race car, the mini-jet, or the hot air balloon?

“This is my thinking,” said Charlie, “if we take the mini-jet we might get there faster but there’s no place to land at the playground. The racecar would be pretty fast, but if we take the hot air balloon we can bring the animal cage to put the tiger in. The cage won’t fit in the car.”

“Excellent idea!” said Henry, a little too loudly, apparently, for they suddenly heard footsteps in the hall getting closer to their door.

The bears jumped back to sit exactly where Lucinda had left them and sat very still, trying to make their glass eyes look blank, so that if Fern peaked in she wouldn’t suspect that they were real live bears with a secret mission in the Teddy Bear Rescue Squad.* They heard the footsteps stop just outside the door, as if Fern had stopped to listen, but then they moved on.

“Quick!” Henry whispered.

“Yea,” Charlie whispered back, “before anyone spots us!”

“’I’ll bring some blueberries!” said Roen, who always enjoyed snacks even during emergencies.

They grabbed the hot air balloon from the closet and hung it out the window, then used the air machine to pump hot air into the balloon, which quickly grew in size. Then they attached the red and blue striped basket to the bottom of the balloon with ropes, and below that they hung the animal cage.

Within minutes they were floating above the house and over the trees as the wind blew them towards the school playground.

Charlie used the spyglass to navigate. “Left, twenty degrees!” he ordered. “Good, now down a bit – WATCH OUT FOR THAT TREE!” They barely missed hitting the top of a big oak tree with its branches that seemed to reach out towards them like arms.

“Look!” Henry squeaked as he peered through the spyglass, “the tiger!”

“Let me see!” Charlie said, taking hold of the spyglass. “Wow!”

Roen had her turn, too. “That’s a big tiger!” she said when she saw the yellow and black striped beast pacing next to the swing set, its tail swishing side to side.

“That’s a big tiger!” Mae said.

Mrs. Moore, one of the teachers at the school, was perched on top of the swing set clutching the metal bar for dear life, staring down at the tiger pacing hungrily below.

The Squad arrived over the playground and hovered there as they worked out a plan. How would they get the tiger into the cage to save Mrs. Moore?

“I could blast it with my stun rocket,” Henry said.

“I could make it fall asleep by shooting it with an arrow tipped with sleeping powder!” said Charlie.

“Let’s cast a magic spell!” Roen said.

Mae stomped her feet and said, “I’ll kick it in the face!”

Everyone looked at Mae, wondering when she’d learned to say something like that and how the tiger would respond if kicked in the face by Mae’s little boot with its silver sparkles and a picture of Elsa from Disney’s Frozen.

All of these ideas could work, they decided, but were a bit risky.

Roen got out her blueberries to have a snack, offering a bowl of them to the rest. They munched the sweet blueberries for a minute, thinking hard to make the right decision. Then Roen had an epiphany, which is like an idea that pops into your head, “I’ll put my blueberries into the cage so the hungry tiger will go in and eat them. Then we’ll slam the door shut!”

Mae piped in, “Then we’ll slam the door shut!”

“Yes!” Henry said, pumping the air with his furry brown fist, “That’s how Grandpa Ted catches groundhogs. If it works for groundhogs, it’ll work for a tiger!”

“But do tigers eat blueberries?” asked Charlie.

“There’s only one way to find out!” Henry said.

“Find out!” Mae said.

Roen was lowered down on a rope towards the cage, which was hanging below the hot air balloon. Being as careful as possible, she attached a bag of blueberries to one side of the cage with tape. Henry and Charlie hauled her back up and she plopped down into the air balloon’s basket. “I’ve never done THAT before,” Roen said breathlessly.

“Well done, Roen!” Charlie and Henry said.

“Well done, Roen!” Mae said.

They positioned the hot air balloon directly over the tiger and—bit-by-bit—lowered the cage down to the playground. When Mrs. Moore saw them, her eyes filled with wonder because Teddy Bears flying around in balloons is not something you see every day.

The tiger looked up and growled, “Who is this who dares disturb my snack time?”

But when the tiger saw the cage and walked towards it, he grew curious. He walked into the cage slowly, further and further, sniffing the bag holding the blueberries.

The tiger growled, “Is it meat?”

“No,” said Roen.

“Is it cheese pizza?”

“No,” said Charlie.

The tiger licked the outside of the bag, curiously. “Is it candy?”

“Much better than candy!” said Henry.

“Much better than candy!” Mae said.

This is when Roen took out her ukulele and sang her blueberry song, “Blueberry, blueberry, bluuuuuuuue…..berry!”

The tiger could not resist. With one giant chomp he bit the whole bag of blueberries right off the back of the cage and chewed, a look of heavenly satisfaction spreading across his big cat face.

Quick as a wink Charlie pulled a rope that snapped that cage shut.

Oh, the tiger did not like being trapped one bit. He roared, blueberries clinging to his huge teeth as he bit the bars of the cage in vain. Mrs. Moore, however, was delighted. She jumped down off the swing set and looked up in gratitude as the balloon—now towing the furious tiger inside the cage—rose up into the sky.

“Who, er, what are you?” she called up to them.

“We’re the TEDDY BEAR RESCUE SQUAD!” they shouted.

Henry, Charlie, Roen and Mae flew over to the zoo and lowered the cage down inside, then fast as birds they fluttered their way back home, let the air out of the balloon and crawled back through a window. It was good they did, because just after they’d sat down in the pile of other toys, Fern (who thought she’d heard something) popped her head into the room. But all she saw was four Teddy Bears sitting absolutely still.

The Zoo was grateful to have a real tiger, something they’d always wanted. They set it loose in their African savanna area so it could roam around freely.

What the zookeepers could never figure out, though, was why the tiger never wanted to eat the bowls of red meat they put in his cage.

All the tiger would eat was fresh fruit, brought in by the truckload.

Over time, the zoo bought four more tigers to add to its collection. On any given day, though, you can easily tell which of them is the tiger that terrorized Mrs. Moore in the playground. It’s the one sitting, its belly stuffed, in a pile of banana peels and bits of blueberries, apples, oranges, grapes and mangos. On Thursdays he gets a special treat of pineapples, which he eats in one gulp. He never ate meat again. Kids visiting the zoo named him Fruity the Tiger. And that, oh my best beloved, is the end of the story.

It turns out lots of grandpas make up stories for their grandkids, and one in particular— Andre Renna, from Lancaster, Pennsylvania—took the idea to a whole new level.

Andre reached out to me through my blog and we had a great conversation in Zoom-land where I learned about his family roots and his storybook grandpa creations. Andre, 70, is a retired engineer and healthcare manager who grew up in a classic Italian-American family in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

“I had the greatest childhood in the world,” Andre told me, “My cousins lived in the house with me. We’d sit on the porch and watch the Mets on TV and have some expresso and sweet pastry. I’d walk to my grandmother’s house four blocks away.”

Andre’s dad was his hero, a solid presence in his life who worked multiple jobs to make sure there was always food on the table, with Italian feasts served up by his mom.

Andre had a close relationship with both his grandfather, a bricklayer, and his grandmother. “I inherited some of my grandfather’s tools— trowels, a hammer” Andre said, “those things are precious to me.”

Andre and his wife raised their two kids in Lancaster, and today they have two grandkids. His granddaughter, Aria, arrived on the scene first, launching a wonderful new chapter in Andre’s life. “She is without a doubt the light of my life,” Andre told me, “Everyone else is a close second. I have a beard because of Aria (Papa, grow a beard!).”

Andre’s #1 wisdom he wants to share with the next generation is to never break a promise. “Your word,” he said, “is the most important thing you have.”

When Aria was 18 months old, she won a stuffed yellow duck at a seaside boardwalk arcade. Aria’s Ducky became a much-loved companion that she carried everywhere — even into her imagination.

One day when Aria was 5, Andre was pushing her on the swing. “And she says, ‘I want to have a surprise birthday party for Ducky.’ And then she disappears because I’m pushing her and she’s still talking, right? We were on the swing for forty-five minutes, and she told me this whole story…”

“Everyone will be at the party,” Aria said, “Penguin, Turtle, Unicorn….”

WHOOSH!

“Flamingo, Snakey and T-Rex and….”

WHOOSH!

“But Jasmine the cat is going to ruin the party…”

WHOOSH!

“In the end Ducky will be OK because he knows we really love him.”

When they went inside, Andre excitedly told his wife the whole story. His wife told him, “Why don’t you write it as a book?” Andre replied, “What the heck do I know about writing a children’s book?”

“Just do it!”

When Andre related this, I was reminded—based on my personal experience—that the smartest thing we can do as grandpas is to listen to our wives.

Andre immediately went to work, embarking on a remarkable collaboration with Aria to create a new children’s book, The Adventures of Aria and Ducky: The Surprise Birthday Party, featuring a little girl named Aria and her menagerie of animals.

The Surprise Birthday Party, a collaboration between Andre and his granddaughter.

He started by simply writing down the story Aria had shared with him; she, along with Andre’s wife and sister, offered up suggestions and corrections to polish the draft. Andre then hired a professional illustrator, David Leonard, to bring the story to life.

For Andre and Aria, the smallest details mattered.

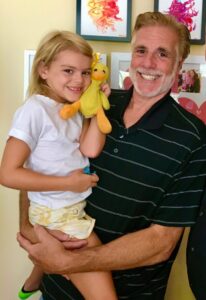

Aria would review the working drafts and say things like, “that doesn’t look like Ducky” or “Jasmine the cat is the wrong color.” Andre was diligent about making sure that the Aria character looked just like the Aria, from facial features to blond hair. “I said to the illustrator, it has to look like her because I want to be able to say, that’s my granddaughter. And in the future I want her to be able to show this to her kids and grandkids. I drove him nuts.” It was worth it.

Andre Renna shown here with his granddaughter, Aria, and Ducky.

When the book launched, Andre and Aria did their own promotional push, appearing on local TV stations and doing interviews for newspapers.

While Andre has sold numerous copies of the book, he’s found a bigger audience by donating copies to pediatric hospitals.

The genesis of the book, with characters based on toys and featuring real children, will have a familiar ring to students of classic children’s literature. Winnie-the-Pooh came about when English author A. A. Milne was inspired by a stuffed bear toy that he had bought for his son Christopher Robin.

But whether or not The Adventures of Aria and Ducky ever becomes well known doesn’t ultimately matter, and the same is true for The Teddy Bear Rescue Squad.

What does matter is that these stories have a chance to become classics in the lives of our families.

I think about the magic of storytelling a lot when I ponder what our grandkids will need in order to become the greatest generation. Many young children live in a world that’s rich with imagination. The couch cushions are their castle walls, a chopstick is Harry Potter’s magic wand. But somewhere along the line—perhaps when they are lined up in rigid rows at school—their flights of fancy become more grounded, their creativity stymied by the need to pass the next test. Yet the truth is that being creative throughout their entire lives may be the ultimate test, the best thing they can bring to their own families, and indeed to employers.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Survey found that creative thinking skills are a top priority when considering talent.

Artificial Intelligence will eat a billion jobs, but the careers of genuinely creative people will be secure for all time.

If we follow the example of Andre and Aria, and A. A. Milne, the next generation will always have their secret forest to walk in, their Hundred Acre Wood, a place where wise owls talk, where the mysterious heffalump eludes even the best trackers, and our favorite bear devours pots of delicious honey. Ducky, Casper, Jasper, Christopher Robin, Calvin, Charlie, Nick, John and Ted will also live in the forest, plus my grandkids and yours, forever and ever.

And that, oh my best beloved, is the end of the story.

Note: If you’d like a signed copy of The Adventures of Aria and Ducky, contact Andre here: awrenna@comcast.net

*Just out of curiosity I recently Googled “Teddy Bear Rescue Squad” and discovered that a woman in England is crafting outfits for a Teddy Bear Rescue Squad. Small world!