For us grandparents, babysitting sick grandchildren is just part of the drill. But could we withstand the dreaded norovirus and puke tsunami? My daughter Abigail and son-in-law Ryan had been…

For us grandparents, babysitting sick grandchildren is just part of the drill. But could we withstand the dreaded norovirus and puke tsunami?

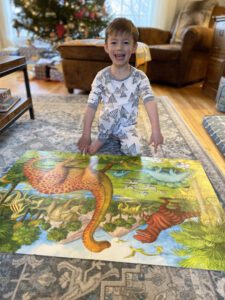

My daughter Abigail and son-in-law Ryan had been having a tough time of it. Grandson Henry—now a long and lanky five-year-old—had come down with a bad stomach bug – the dreaded norovirus. So bad he’d been vomiting non-stop to the point where dehydration gave him double vision.

Abigail was deeply tired and stressed out caring for poor sick Henry while our youngest grandson, Charlie, still demanded attention (as three-year-olds do).

Abigail brought Henry to the emergency room where he needed to be attached to an IV to get rehydrated.

Her stress permeated anguished texts that described how she and several nurses had to hold Henry down as he thrashed and howled when they put in his IV. Henry had screamed, “Help me!” and all Abigail could do was keep holding him down for his own good.

“It’s so hard,” we texted back, “we know.”

I was brought back to the time I had to hold down our 6-year-old son, Nicholas, when he needed a spinal tap to diagnose meningitis. The procedure was so traumatic the doctors gave Nicholas a drug so he’d never remember the experience. I thought, “Where’s my drug?”

Henry made a speedy recovery, just in time for Charlie to come down with the same bug; he began vomiting (apparently all over the place). Abigail’s dog, Rory, was also puking.

To make things even more stressful, Abigail and Ryan had a tropical getaway planned for that weekend.

We grandparents had been lined up months in advance to babysit, and were determined to help them get far from the December New England chill and the puke tsunami.

When we arrived, Charlie was still sick with a fever and totally miserable. He kept saying, “My tummy hurts,” and instead of doing his usual routine—running laps around the house—he was curled up on the couch. Rory kept making “gak” sounds from deep down in her throat as if on the verge of bringing up dog chow like a fire hose. Henry wanted someone to read him a book. Or play Frosty the Snowman on the Kindle. And get him a cup of milk. The picture window in the living room showed the dreary tangle of maple trees in the sloping back yard, grey-brown leafless trunks darkly wet in the slanted curtain of freezing rain and snow.

“I feel so bad leaving you with all this,” Abigail texted from the plane.

“Don’t worry,” Nancy texted. “We’ve done this before.”

Walking into this environment where one touch of a microbe-infested doorknob or sniffle might lead to days of feverish hurling was just part of the drill. Mere mortals would have been excused from this duty. After all, if a five-year-old got so sick he required hospitalization, what would the norovirus do to a sixty-year-old like us? This bug is known for being extremely contagious and tough to kill. It can live on a toilet handle for two weeks, and is so resilient it just laughs at Clorox wipes. The only thing that kills it is industrial-grade bleach like you’d have in the rescue truck along with your hazmat suit in a Congo contagion zone.

Over the course of the next three days we gave Charlie Tylenol and stroked his back, read many books, and watched Rudolf the Red Nosed Reindeer and other Christmas favorites.

We did dinosaur puzzles and other activities – taking frequent breaks to scrub down our hands with hot water and soap like surgeons.

It kept raining and snowing for days, a nasty wintry mix. And all the while we’d see Abigail’s Instagram stories with her and Ryan’s smiling faces bathed in warm sun, drinks in hand at a beach.

Each picture of Abigail happy and rested was a thank you for the gift that we had brought, this gift that sometimes only we grandparents can provide. A blessed break from it all. A chance, however brief, to relax and take a deep breath. To bask in the sun, knowing that the kids were ok. More than ok, actually. In very experienced hands.

Sitting in the living room in dark Connecticut where the dog was going “gak!” and Charlie was moaning and Henry wanted attention and the cold rain tapped against the windows was a pleasurable duty—an expression of our love and commitment—and I could feel that tropical sun on my face with a warmth I can never fully measure or convey in mere words.

Abigail and Ryan returned after three days, and Nancy and I headed back to Boston. That night Nancy’s stomach started to hurt very badly, and soon she was praying on her knees to the porcelain God, her temperature 101. I tucked her into bed, wondering if I would be next.