Author’s note:

When I was a boy my father took great delight in telling me stories at bedtime. Sometimes they were his old favorites, like Winnie the Pooh or The Wind in the Willows. But many nights dad would make up his own stories on the spot. His extemporaneous tales were wildly imaginative and each was very different, but all of them involved two main characters—ghosts named Casper and Jasper—along with me and my four older brothers. I lay in rapt attention as each story unfolded, delighting to hear new stories where I and my brothers had roles to play.

Unfortunately none of these stories was ever written down. That was part of their magic, I suppose. They were like unique flakes of snow that spun magically and melted on my mind, never to be seen the same way again. I don’t remember what happened in the stories, but I do recall loving them. And loving the time I got to spend with my father, a man who was always busy with a million projects.

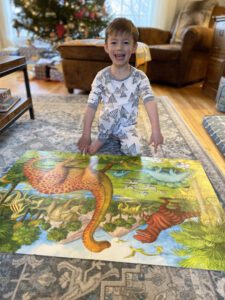

Now, with three grandchildren and one more on the way in February, I’m following in dad’s footsteps. When my own kids where little I made up stories, and did write some of them down (they’re probably in a box in the basement somewhere). But today with the grandkids I have a chance to make my stories more evergreen, and share them with your family as well.

Here, then, is one such story. My two main characters are Henry and Charlie. To me, they are my handsome, smart and fast-growing grandsons. To everyone else they may be simply characters, but I hope that they are as real for you as they are for me.

Enjoy,

Grandpa Ted

It was a day like a lot of other days in Oakdale, Connecticut.

People drove around and bought groceries or shoes. They had Zoom meetings in the basement laundry room, ate macaroni for lunch in front of the TV and had naps or played video games. Henry and Charlie, however, were not going to have a regular day. Why?

Well, I just don’t know where to begin. So I’ll start at the beginning.

Henry, age 6, and Charlie, two years younger, woke up early and went downstairs to play. Pretty soon mom, otherwise known as Abigail, came down and asked if they would like to have one of two things for breakfast. Option 1 was blueberry pancakes. Option 2 was a new kind of breakfast burrito made with BongoBongo beans, grown only in the heart of the great Amazon forest in Brazil where the trees grow very tall.

The boys were tempted by the idea of pancakes, but they’d JUST had them the day before and today they felt like something different.

So they asked for the special Breakfast burrito with the Brazilian BongoBongo beans.

Mom said, “Coming right up!” And within minutes, Charlie and Henry were chowing down on their BongoBongo bean breakfast burritos like dogs who hadn’t eaten in months. They made so much noise eating that their next-door neighbors, Claire and Carl Loosebowel, came over and complained. The Loosebowels were short with wiry black hair, and tended to run everywhere they went.

Charlie looked closely at one of the BongoBongo beans. It was bright yellow and as big as a grape but longer. And it tasted like a combination of chicken and marshmallows.

After they finished devouring their BongoBongo bean burritos (more quietly so as not to disturb Claire and Carl Loosebowel) they went outside to play in the snow.

It had snowed about two feet earlier in the week, and Henry and Charlie had built a big snow fort which they named The Kingdom of Wow.

Well, on this day—which, as I’ve said, was definitely not a regular day—the boys discovered their Kingdom of Wow was for some strange reason way too small to get into. The snow fort had apparently shrunk overnight to about half the size it had been. Disappointed, the boys went inside to tell mom. But just as they were walking into the living room both Charlie and Henry bonked their heads on the ceiling.

Mom looked up at them and her jaw dropped in wonder.

Henry said, “Hey, the Kingdom of Wow shrank. We can’t get in! And why is the ceiling so low in here?”

Mom said, “Oh my. You are so much bigger than you were when you woke up. How is that possible?”

Henry said, “What?” But when he looked at the family dog, Rory, he knew it was true because Rory was now the size of a tiny toy poodle.

Charlie was about to say, “We can’t be getting big that fast, can we?” Even as he was saying this he saw the room shrink before his eyes and felt the top of his head pressing harder up against the ceiling.

“Goodness,” mom said, “You better go outside!”

They ducked under the front door and as soon as they were outside the trees lining the road seemed to shrink down to little shrubs. A sparrow flew by and landed on Henry’s shoulder. Farther and farther down below cars drove through the neighborhood like tiny Matchbox race cars. Charlie looked up at a cloud and before he could say “what the…” his head was in the cloud.

Henry and Charlie’s dad, Ryan, came out on the lawn and looked up at the two fast-growing giants and immediately pictured his sons with college basketball scholarships. With Henry and Charlie now taller than the house, they’d be able to get the basketball in the hoop every time.

Abigail couldn’t believe her eyes.

Henry and Charlie just kept growing and growing, way bigger than their Grandpa Ted. They were now as tall as buildings and they kept right on going. Henry heard a buzzing sound which he thought was a bug going by his right ear, but when he looked he saw that it was an airplane. People on the airplane had their faces glued to the windows as they looked out at him in wonder.

“Um, what’s going on?” Ryan asked Abigail.

A bunch of ideas ran through Abigail’s mind like frantic mice.

Then all at once she knew what had happened.

“It was the special Brazilian BongoBongo beans in the breakfast burritos!” She blurted.

“Really?” Ryan said.

“That has to be it!” Abigail said. “They must be some kind of magic bean that makes children grow!”

By the time Abigail said this, Charlie and Henry’s feet were bigger than the Subaru parked in the driveway. The boys looked at each other and laughed. “This is so cool,” Charlie said. “Yea,” replied Henry.

Just then Henry burped, sending a gust of burpy breath so strong it made a nearby helicopter fly wildly off course.

The boys kept right on growing.

And growing.

And growing.

And still they grew, higher and higher. They looked up, wondering how high they could possibly go. The sky above was no longer blue. It was increasingly dark like a cloud, yet clear at the same time, with little specs of white twinkling out of the darkness like the fireflies the boys had seen blinking in the air on cool June nights in Vermont.

That’s when they realized the lights were stars.

Suddenly just like that their heads popped through into space. They had never seen stars and planets so clear before. Especially the moon. The surface of the moon wasn’t smooth after all. It was not a round flat ball of white like they’d seen out their window at bedtime, but a place with mountains and valleys, and maybe even lakes of dark green blue water shimmering in the sun.

At this point the boys were so big they were able to reach up and grab hold of the moon, and with one big pull they managed to hoist themselves up and set foot on the moon for the first time. The ground was made of grey powdery dust. A small American flag stood a few feet away, with a few stray golf balls around it.

On the horizon the Earth looked like a little blue ball.

That’s when they heard footsteps. Not just any footsteps. GIANT footsteps, each one making a huge crashing sound.

“Hide! Quick!” Henry said. They ducked behind a mountain just in time, because the next second a humungous cat — bigger than a building, bigger than the mountain they were hiding behind, bigger than anything they’d ever seen slinked into the valley. Its fur was brown streaked with rivers of sickly mustard yellow. Its eyes gleamed white like the headlights of an oncoming truck. Its teeth were long and spiked like knives.

The cat growled,

“I’m a kitty who has no pity

Hear me purr while I eat your city

Munch and crunch

Scratch and prowl

When I’m done, you won’t look pretty.”

Charlie grabbed Henry’s arm. “Can we go home now?” he pleaded in a hushed voice so the giant cat wouldn’t hear him.

“Wait,” Henry said, “Look!” He pointed to a little thing that was following the gigantic cat. “It’s a kitten.”

Charlie said, “Oh, so cute.”

“We have to take him home with us” whispered Henry.

The question was, how could they get the kitten without the giant cat seeing them?

This was quite a puzzle. Should they scrunch down and crawl over to grab the kitty? No, the giant cat would spot them in a second. Should they catch the kitten with a net? Well, they didn’t have a net. As the huge cat sat and licked its claws, Charlie and Henry sat and thought. And they thought some more.

That’s when Charlie saw a bush next to him, and hanging from its branches were BongoBongo beans just like the ones he’d had in his Brazilian BongoBongo bean burrito that morning.

Maybe the beans weren’t from Brazil after all. Maybe they were from the moon!

Charlie picked a BongoBongo bean and munched it, savoring the chicken marshmallow flavor. And suddenly right before his eyes Henry grew. Or he thought he grew, but in reality what had happened was that Charlie had shrunk, for in his eyes Henry was now a giant.

“It’s the BongoBongo beans,” Charlie said. “They made us big at home, but on the moon they make us little.”

Henry knew in an instant that Charlie was right. “Hey,” Henry said. “If we’re little we can sneak up behind the giant cat and get the kitten without him even seeing us!”

Henry reached for a BongoBongo bean so he could get small, too, but then it dawned on him that if both he and his brother were little they wouldn’t be big enough to reach up and grab hold of the Earth to pull themselves back to Connecticut. They’d be stuck on the moon forever. The boys talked and came up with a plan B. Henry would just have to stay big, they decided, while Charlie would stay small.

“Ok,” said Henry, “I’ll go distract the big cat while you sneak in and grab the kitten. Then run as fast as you can back to this spot and I’ll get us home.”

So off they went, Henry towards the front of the big nasty cat, and Charlie towards the kitten behind.

Henry walked bravely right up to the giant cat.

“Hey, you big ugly cat!” Henry shouted up at the creature.

The cat’s head turned and as it spotted Henry before him its eyes narrowed and it bared its huge sharp teeth. A hiss like a thousand snakes poured from its mouth.

“Who dares enter the land of the moon cats!” roared the cat. “Speak, or I’ll make you my purrrrrrfect little snack.”

Henry planted his feet defiantly and held his hands behind his back. “My name,” he said confidently, “is Henry. What’s yours?”

“I have no name that you would understand, little snack child,” said the cat. “I am Lord of the Moon Cats. I lay in the warm sun. I prowl the moon night and day. I catch and eat things. I claw furniture without getting into trouble. I answer to NO ONE. Tell me your business quick.”

Henry spotted Charlie running behind the cat towards the kitten, his feet kicking up little clouds of moon dust. Henry had no idea what to tell the big ugly cat, but he knew he had to stall him to give Charlie more time.

“My business?” Henry said. “Funny you should ask. I have very important business. I have to…I mean, what I have to do here, the business is….well, you see…”

“You have five seconds!” screeched the cat, raising a paw and baring its claws.

“Well, since you asked,” said Henry, “I’ll tell you.” He saw Charlie grab the kitten and run.

“I have been sent,” Henry said, “on a mission from the planet Earth; that’s the blue dot up there,” Henry said, pointing calmly, “a mission to find the smartest cat in the universe.”

The giant cat, who had been ready to swipe Henry right off the ground and into his mouth, paused. In truth the Lord of the Moon Cats had always thought of himself as quite smart. He had, after all, out-smarted all the other moon cats in order to become Lord of All. He usually won at board games and was very good with crossword puzzles. The thought of everyone on all the planets realizing that he was in fact the smartest cat in the universe was tempting. He wanted to know more — although his tummy was starting to rumble with hunger and he was not known for patience when it came to snacking.

“Go on…” said the cat.

“Well, yes, of course,” said Henry, wishing at this point he’d never gotten anywhere near this giant beast of a kitty.

“You see, once we’ve found the absolute smartest cat, we will give it a new planet to rule, and provide it with the best cat toys to play with, plus all kinds of delicious food night and day so it will never again have to hunt for things to eat. It will be able to lie in the warm sun and nap all day AND all night. Now, to see if you might be the smartest cat, you’ll have to take a test and….”

“I take no tests!” screeched the cat, rising up on its hind legs.

“I’m the Lord of the Moon Cats! Only I give the tests that others must pass! So I will ask YOU three questions. If you get them all right, I will be declared the absolute smartest cat in the universe!”

“Ok,” said Henry, “But you must promise not to eat me.”

The cat rolled its eyes, “Oh fine. Here’s question number one. How do you spell cat?”

Henry had just studied this at school, but he was a little nervous with the giant cat breathing on him. He thought and thought.

“Cat begins with. Um, it begins with…C!” shouted Henry.

“And then what?” the cat said, its claws drawing nearer.

“C-A-T!” Henry squeaked in a nick of time.

“A lucky guess!” said the cat, disappointed but still quite sure he’d be eating the boy soon enough. “Question two. What is five plus four?”

Henry counted on his fingers behind his back.

“Eight!” said Henry, “No, nine! Five plus four is nine!”

The cat, which had started licking its huge purple lips at the thought of chewing up Henry, hissed with a great gust of nasty smelling cat breath that nearly knocked Henry off his feet. “Clever boy!” said the cat, “But my last question will be hardest of all, and when you get it wrong I will eat you!”

“Ready!” said Henry, wanting very much to run.

“What colors do you mix to make pink?” the cat asked, raising an eyebrow.

Henry froze. He thought back to all the art projects he’d done with his mom.

They’d mixed all kinds of colors together to make brown, black, yellow, blue – but how did they make pink? Seconds went by. The cat inched closer to him and Henry could hear a low rumbling sound, the gurgle of the cat’s stomach.

“Red!” blurted Henry, knowing at least that red was definitely part of pink.

“Red and what?!” said the cat, coming even closer.

Henry’s mind raced. He knew it wasn’t blue or green or orange. But if red was just a lighter shade it could be pink, yes? What could make red a little less red? Just then he looked down at his feet, thinking hard, and there by his right foot was a white rock.

“White!” shouted Henry. “Red mixed with white make pink!”

The cat jumped up on its hind legs and roared in frustration, clawing the air.

Henry bolted. He ran harder and faster than he ever had before, and when he looked behind him he saw the big kit coming towards him, bounding from mountaintop to mountaintop and gaining on him.

Henry jumped across one final hill and found Charlie crouched by a boulder, the kitten in his arms. He grabbed Charlie and the kitten and jumped lickety-split up towards the blue ball of Earth and managed—just barely—to grab hold of it and pull himself up with one arm, but when he looked down the giant cat was in mid-air jumping after him with one huge paw raised to strike.

The ferocious moon cat’s paw, with claws outstretched, swished with a rush of hot air within inches of Henry’s feet, barely missed him. And with one last pull Henry lifted himself and his brother and the kitten back to the yard in front of their house in Darien, Connecticut.

They were home and safe at last.

The only problem was that Henry was still as tall as a skyscraper and could not fit in their house, while Charlie was regular size.

But it turns out there’s a solution to everything. Because they soon found out that the moon kitten, who they named Bongo, pooped silver dollars. Lots and lots of silver dollars. So the boys gave them to mom and dad, and with all the extra money they built a huge addition on their house just for Henry. (Truth be told, they kept a few dollars hidden in a piggy bank to buy candy with, or cat toys for Bongo).

Charlie and Henry would play together as they always did before their BongoBongo bean moon adventure. In time, of course, Charlie grew to be just as big as Henry. And at some point every day, after playing and playing with all their toys for hours, they’d give each other a hug.

“No matter what,” Henry would say, “You’ll always be my best little brother.”

“And you’ll always be my best big brother,” Charlie would reply.

And Bongo would always be the smartest little moon cat there ever was.

THE END

#grandpa

#grandfathers

#grandparenting