Seven years ago when I found out I was going to be a grandpa I immediately sought advice on grandparenting. The prospect of being a grandpa seemed daunting. Surely there were a million things for me to learn. Books to devour. Professors to consult.

But first, I spoke with my Aunt Lois.

Lois, now 95, is my late mother’s sister. In her career Lois was a much-loved music teacher as well as an accomplished cellist. During WWII she became a pilot to help ferry mail across the United States.

Most importantly, Lois has 6 grandchildren and 5 great-grandchildren. So I asked Lois for advice on how I could be a good grandfather.

Lois looked thoughtful for a moment, raised one hand and pronounced with gravitas, “Be there for them.”

At first I thought this was just the preamble to a speech. Nope. “Be there for them” was it, not so much a statement as a command. I have done my best to live up to this deceptively simple advice.

Being a grandpa has meant not sitting on the sidelines.

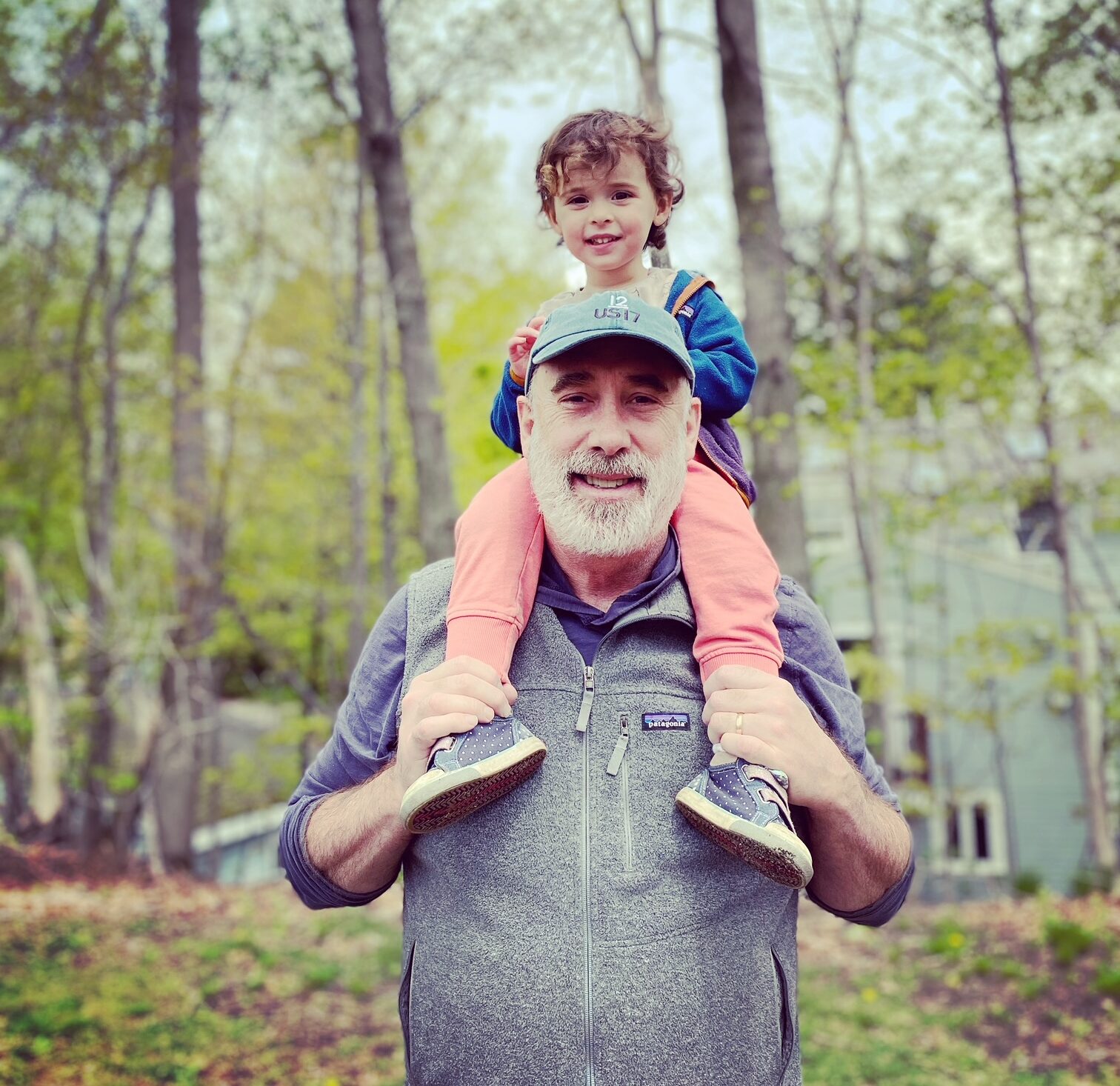

When I take the grandkids to a playground I’m there to play with them, not chill on a bench. In one of our favorite games I play the role of the “Tickle Monster.” I run around trying to catch them, and when I finally do (which requires real work given how speedy these kids are) they get tickled without mercy. Peals of laughter can be heard for miles. But like any good fisherman I release the little ones so they can be caught again.

Hanging out with the kids at home entails all kinds of activities together. Like creating castles out of couch cushions. Or reading The Lorax while snuggled up on the couch first thing in the morning as they glurp milk from sippy cups. Or Goodnight Moon at bedtime, the sound of my voice gradually lowering with the sun to lull them towards sleep and the realm of dreams.

All of this came to an abrupt end at the dawn of the pandemic.

It’s been said (notably well by the writer Paula Span in her article The Year Grandparents Lost), that the pandemic was especially hard on grandparents. Not only did the pandemic cause more deaths among older age groups, it also built a wall between the generations just when everyone needed their loved ones the most. For my wife and I, being apart from our children and grandchildren felt like being exiled to a foreign land. Some kind of Siberian gulag of the soul. Fortunately my wife has proven to be an excellent pandemic buddy despite her leaving countless balls of used Kleenex around the house strewn like wet flowers after a storm (truthfully, the list of my transgressions would require an entire story all to itself, but somehow she puts up with me).

Playground romps and bedtime books were replaced by rations of Zoom and FaceTime. It’s not that the video chats were infrequent; we were jumping on the phone multiple times every day. But too often our calls seemed like constant reminders that we could not really be there with our grandkids.

And all the while we knew they were growing up without us.

That hurt. Still, we reminded ourselves that our parents’ generation had it a lot worse; they lived through the Great Depression and a horrific world war. Surely we could manage through the masks and isolation.

Job one was simply to stay alive. In the case of my mother-in-law, Dorothy, this was unfortunately not possible. After months of near total isolation in a nursing home she succumbed to COVID, alone, in a Providence hospital in September of 2020. Her tragic death made us double down on our resolve to stay safe so we could one day all be together again. Which meant staying alone.

The surprising chorus that ushered in the spring of 2021.

I went to get my first shot of the Pfizer vaccine in March. It was in a big open space of a community center on the North Shore of Massachusetts, buzzing with nurses and volunteers and people like me. For months I’d seen the absolute misery and pain of front-line healthcare workers struggling to help COVID patients in the face of short supplies and overwhelming caseloads. But in the hall that day a different mood prevailed. The space was suffused with hope and happiness, and while I could not see the smiles under the masks of the nurses, their eyes spoke volumes. At last here was something positive and meaningful they could do.

After the quick jab I sat in the hall for the required half hour. And it was there, as I thumbed through emails and posted on Facebook, that a song welled up on the loudspeakers. It was Bill Withers singing Lean On Me. Quiet at first, then building as one by one, like a wave, the nurses, volunteers and patients started to sing along.

“Sometimes in our lives

We all have pain

We all have sorrow

But if we are wise

We know that there’s always tomorrow

Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend

I’ll help you carry on

For it won’t be long

Till I’m gonna need somebody to lean on…”

Behind the big sheets of plexiglass the nurses sang and swayed to the music, this rapidly growing chorus of those who had been beat down but were now rising, together. I sang, too. It was an electric feeling, a moment I will never forget.

“Please swallow your pride

If I have things you need to borrow

For no one can fill

Those of your needs that you won’t let show…”

Within a few months, the second vaccine shot behind us, my wife and I were finally able to see our children and grandchildren again. There were many hugs and tears.

“Lean on me when you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend…”

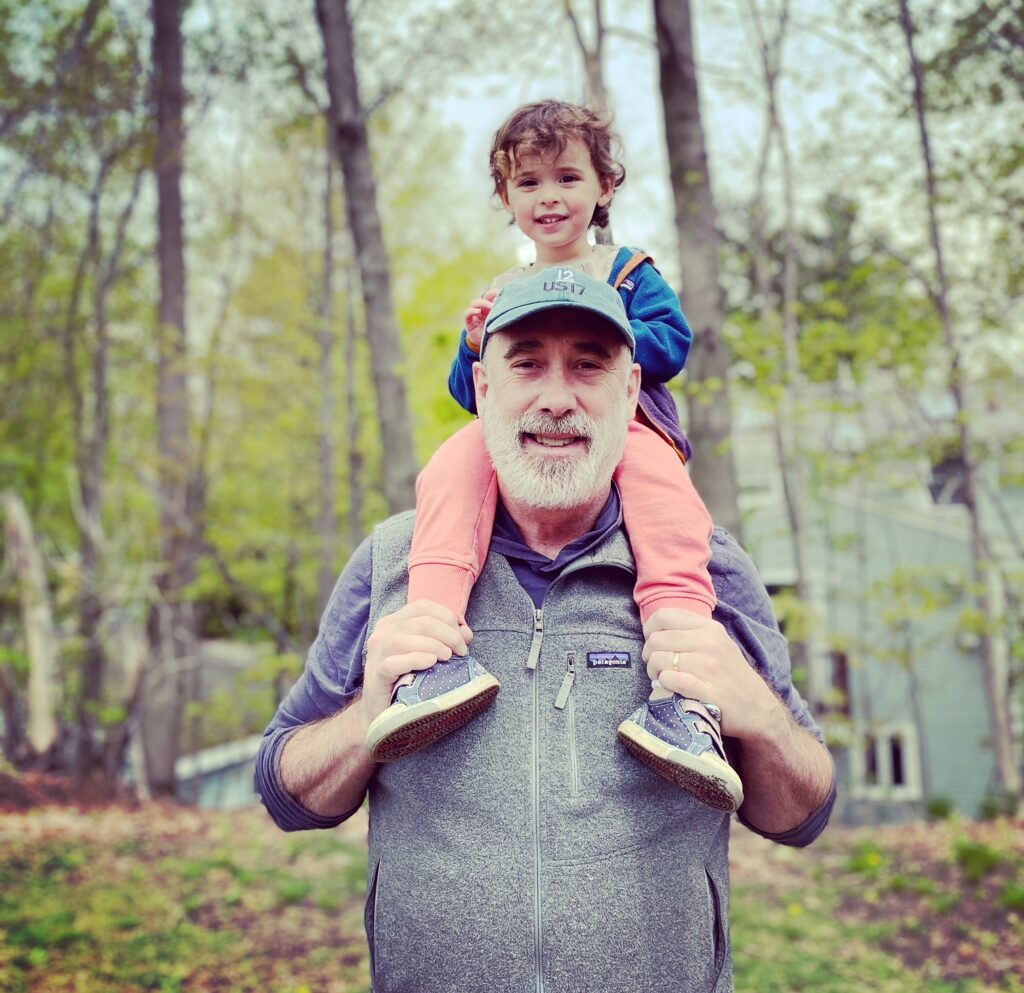

In a way, our grandchildren seemed the same (although bigger). But when my oldest grandson—now 6—grabbed a book so we could read together, it was now him proudly reading to me. The gap of time we’d lost together was suddenly palpable. This made me sad, yet I was also happy—filled with joy, actually—because despite the many challenges of the past year our family had continued to grow and persevere. Our bonds had become even stronger. And once again, with the love and support of all those around me, I can be there for them.

“I’ll help you carry on…

For it won’t be long

Till I’m gonna need somebody to lean on.”