On December 3rd, 1947, the blond-coiffed professional wrestler known as Gorgeous George ascended into the ring of the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, basking in the applause and jeers of…

On December 3rd, 1947, the blond-coiffed professional wrestler known as Gorgeous George ascended into the ring of the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, basking in the applause and jeers of the massive crowd.

He was joined in the ring by his opponent, a six-foot-tall muscular black wrestler who went by the name of Reginald Siki, sometimes called The Panther. The instant the starting bell rang, George ran at Siki, took a flying leap and delivered a dropkick to his chin. Siki obligingly collapsed, ending the match after only 12 seconds. Gorgeous George’s path to fame accelerated, his telegenic theatrics a perfect match for the burgeoning age of television.

Siki would be dead within a year, a relative unknown today, yet far more deserving of recognition. Siki won numerous matches in this career, but due to the color of his skin his name was never entered in the record books.

Born Reginald Berry in Kansas City, Missouri in 1899, Siki was—according to a fascinating article in Slam magazine—among the most prominent Black athletes of his day, achieving fame largely in Eastern Europe where he could escape from the rampant racism of North America (in Canada the press once dubbed him “gorilla man”).

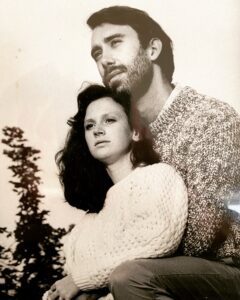

After performing for a stretch in Germany in the months leading up to World War II, Siki and his wife were arrested in 1942 and imprisoned in Tittmoning, a Medieval castle in Bavaria along with hundreds of Americans. Siki nearly starved to death. At one point, a fellow inmate, Max Brandel, drew a caricature of him which Siki inscribed with the words, “Let’s keep going.” Brandel became a contributor to MAD magazine (“What, me worry?”).

I learned the story of Siki when I met up with his great-great grandson, James Lott Jr., in Zoom-land recently to further my deep dive into the varied lives of grandpas.

James, 55, has a detonation of black hair that expands out in all directions, a neatly trimmed white goatee, and a vibrant and friendly personality. He has a whole string of letters after his name—CTACC CDC LVN PMO OA DD—that speak to his thirst for learning. “I’m a chameleon of many sorts,” James said. I’d call that an understatement. James is the CEO and Founder of JLJ Media, the CEO and Founder of Super Organizer, certified as a professional organizer and life coach, holds a nursing degree and a PH.D., has done acting gigs on commercials and an episode of House (season four, episode four), has his own YouTube channel, and does a podcast called Really! I’m a Grandparent!. James, who’s single, lives in Englewood, California, and stays close to his many nearby grandchildren.

James started his career as a farm and agricultural insurance specialist, but during the recession of 2008 he had a major epiphany.

“I realized I hated my job,” James told me, “hated everything in the city, my kids were grown and I’d already become a grandfather. I decided to change my whole life.” He made a list of all the things he loved to do, “I like filing. I like organizing. I like people. I like media. I don’t mind speaking in front of people. So I talked about it with my grandfather’s sister, and she said, There’s a business in there. Entrepreneurship!”

James moved back to his family home in Los Angeles and started Super Organizer L.L.C., providing organizational services to a growing roster of clients that today includes movie stars.

He also followed his passion for video and podcasting, with a flair for being on camera, through his media enterprise. The media world is James’s version of the Forever Letter. “My grandkids know me as this person who talks to celebrities. When I die, they can just go online and see their grandfather.”

When I learned that James became a grandpa at the tender young age of 39, I said, “Wow, I thought I was young at 55 when my first grandchild was born. You were way ahead of me!”

“Here’s the deal,” James replied, “I started my podcast because I saw the face of grandparenting has changed. My show is for young grandparents. I come from a long line of them. I grew up with grandparents who still jogged and dated and were having kids.” When James told me this I tried, and failed, to imagine the grandparents in my life jogging. The only time I could see them moving that quickly was to run away from bears.

One of James’ grandfathers—Grandpa Bob— was an executive with Chase bank in Manhattan.

“He was young, a Rolling Stone,” James said, “dressed very sharp, smoked a cigar, totally New York, the whole thing.” James’ other grandfather was white and Dutch, a little older, with a white beard. “My two grandfathers were like chess pieces on opposite sides of the board.” One of James’s youthful grandmothers would start her day running ten miles and swimming five. She drove a sporty Karmann Ghia (my Gram, in her late 70s, drove a vintage pink Rambler, cheerfully oblivious to the concept of lanes).

Through his podcast, James has connected with all kinds of young grandparents. “I’m meeting more and more people in their 30s and 40s who are grandparents,” he said. “It’s no big deal in their lives. It’s like, ‘I had a daughter at 18, and she had a child at 18.” Being a single grandpa who’s active in the LA dating scene is also a different ballgame. “I never know when to bring it up,” James said. “Sometimes it comes out organically, like, What are you doing this weekend? I’m seeing my grandkids in Sacramento. It’s a mixed reaction.”

James also sees that many of today’s youthful grandfathers are playing a larger role in the lives of their grandkids.

“I always think it’s a generational thing; a lot of times the grandmother is seen as the nucleus of the family, but there are some good grandfathers out there who do run families. It’s part of my mission to share that.”

“The second thing for me,” James continued, “is the multiracial aspect. I have grandkids that look the spectrum from blond hair and freckles to brown.” During the period of civil unrest after the George Floyd killing, James had honest talks with his grandkids about the police based on his own negative experiences. The brown grandkids had a different talk than the blond ones. “But the Gen Z’s and Gen Alphas,” James said, “they’re actually not caught up in all that suff. We’re the ones caught up in it—we Boomers and Millennials. My grandkids have a set of friends whose parents were same-sex. Their first President was Black. So, their whole outlook is different.”

James has found there’s a generational shift in perspectives on work-life balance as well, with many young people choosing educational and career paths outside the norms pounded into us by our Greatest Generation parents.

“These kids are saying, you want to pay me $10 an hour to do that?” James said. “They’re questioning. Some are choosing trade schools instead of college. I was taught to work at a job until you’re 65 and then you retire and travel. I’m actually impressed with how much these kids don’t care about certain things that we’re holding on to. They just want to live their lives. They’re going to do it their way.”

This idea resonated with me—a lot—when I thought about it within the context of nurturing the next great generation.

Being fully accepting of differences and unconstrained by old-fashioned career paths seem all part of the same new vision. And these changes seem to be happening naturally as a result of the guidance and wisdom we gave our children when we were young parents. We—and I mean ‘we’ in the larger sense meaning so many parents everywhere—taught our kids to treat everyone the same. We also encouraged them to choose the career that would allow them to do what they loved, even if that meant making less money. By the time our kids left the house as young adults, we’d largely completed our job. And through that parenting—ours and James’s alike (and yours)—the newest generation is already greater in many ways than any that came before.

James summed it up best when he said, “They have the freedom to live a different life.”

This doesn’t mean we grandparents can’t continue to play a strong supportive role. We can help lead a discussion about generational greatness. And we will always be the elder Maple trees who’s leaves nurture the seedlings. We can be there for them. But we have to be careful not to preach to them like we know everything, because we don’t. Tom Brokaw said he learned more from his grandkids than they’ve learned from him. Wise words.

I saw this principle on glorious display on a warm July day a few years ago on the shores of Lake Willoughby, a place I will continue to return to in my upcoming book. All of our grandkids and their cousins where down at the beach with their parents and everyone was buzzing with excitement because we knew that this was the day that my cousin’s son, William, would become engaged to his boyfriend, Brendon. The plan was that Brendon would take William out on their vintage wooden motorboat and pop the question. The grandkids made signs of congratulations that they could hold up when the boat returned to the shore, and sure enough, an hour later as the boat approached—William and Brendon beaming—the grandkids jumped up and down on the dock with their signs, shouting “Yay!” and “Congratulations!” and “We love you!”

Nobody on the beach that day had to explain that William and Brendon were different, that they were gay.

Because they are, in fact, no different than any of us. They are simply a young couple in love, one that is today happily married.

Before James and I parted ways in Zoom-land, I asked him for his #1 piece of wisdom for the next great generation. He instantly said, “You can survive anything. Life isn’t fair. Life is tough. Life is wonderful. It’s all those things, three dimensional. I wish I could have told myself that when I was 18. Just don’t worry, James. You will go through a lot of stuff, but you will survive, and that’s what I tell my grandkids.”

Our ancestors continue to shape who we are now, through genetics and remembrance. When James talked about survival all I could picture was the greatest wrestler of the 20th century, the indomitable Reginald Siki, languishing in a German prison camp, so hungry he lay still to conserve energy, yet he smiled as he looked at the caricature drawn of him and wrote the words I will say to my loved ones any time our multidimensional lives get tough: “Let’s keep going.”

Author’s note: Be sure to check out James’s Really! I’m a Grandparent Podcast. James had me on his show, even though I’m not a young grandpa these days (thank you, James!). Also, if you or someone you know has a grandpa story to tell, please reach out to me at ted [at symbol here] GoodGrandpa dot com. I’m writing the Good Grandpa book for Regalo Press which will be distributed by Simon & Schuster in mid-to-late 2025.