My mother really wanted to have a girl, but… After giving birth to my four brothers she tried one last time, and had me. Then she gave up and got…

My mother really wanted to have a girl, but…

After giving birth to my four brothers she tried one last time, and had me. Then she gave up and got a girl dog (Holly), as if this was her way of telling Mother Nature that here, at least, she had some control over things. But Holly was just one small female addition to a situation that was never in control. Today as a grandfather of two grandsons, I understand the special chaos of boyhood, and see it through the lens of my own experience as a brother.

Brothers in an explosive childhood.

Growing up in a house with five brothers, all gigantic and constantly ravenous, was like being in some kind of nature preserve, only the walls could not keep us from spreading our particular brand of mayhem throughout the town of Lexington. My eldest brother, Calvin, made a habit of hacksawing the tops off of the parking meters and using the timing device on his homemade pipe bombs. It didn’t help matters that my father, a chemical engineer, built a full chemistry lab in our basement. Explosions were so frequent that we barely flinched when a bomb went off that shook the whole house.

There was chemistry in our birth order as well.

Calvin was the eldest troublemaker, so much so that we later in life suspected he was the Unabomber. Next was Charles, an Eagle Scout who was always trying to stand up to Calvin, as if saving us from Calvin’s bombs would earn him another merit badge. Then came Nick, the middle brother, who saw himself as the diplomat between his two older brothers, and the two youngest—my brother John and lastly yours truly, sometimes not-very-affectionately referred to as Baby Teddy. John spent much of his childhood looking torn between abject terror and complete indifference. And I, running along behind them all as the firecrackers stuffed into the walls of the makeshift dam in the backyard exploded, was the spectator to the greatest show on earth.

A trial by fire.

We brothers finished each others’ sentences. We tried and failed to avoid each others’ farts. We knew where the older brothers’ Playboy magazines where hidden. We climbed mountains together, and ran down. As the youngest, I wore their hand-me-down shoes, and I cried when they left for college.

In Shakespeare’s Henry V, the King rouses his troops to carry on the battle—

“This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd—

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.”

I don’t think it a coincidence that the greatest writer the world has ever known used brotherhood as the ultimate clarion call of unity and love. We five—Calvin, Charles, Nick, John and me—were our own band of brothers, we happy few who thought nothing of devouring an entire pot of macaroni at one sitting, or shot cannons (no, really) packed with gunpowder and nails, or combined the gasses from an industrial blow torch to fill balloons that made terrific explosions when ignited; a trial by fire it was, with mom and Holly, the family’s sole representatives of humanity’s better half, seeking cover.

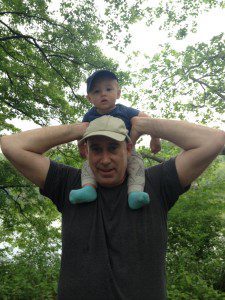

When I see my grandsons, Henry and Charles, playing and laughing, all of my memories of the times I played with my brothers are right there in the room. The toys my grandsons play with (Paw Patrol!) may be new, yet the dynamic of play is the same. There are times when they will fight over a toy, but I know that behind every shout of “Hey, that’s mine!” is a deep appreciation of what is theirs together, a common adventure into adulthood they will never forget.