Hiking was always a big deal in my family growing up.

My dad loved to get out on the trail with me and my four brothers, trekking up through the thick forests of New England until we rose above the tree line to see the panoramic views. Or no views at all during those rainy-day hikes when staying home was never an option. For dad, being outdoors and moving, breathing hard up the steepest and most rocky slopes, was a balm for his soul. He was one of the many WWII vets who was more traumatized by his war experiences that he ever wanted the world to know about. Every year on Hiroshima Day, August 6th, he’d take us on a hike up Mount Washington and remind us, again, that there was no way to justify the use of atomic weapons on anyone. He’d say, “There’s always a way to rationalize cruelty.” It was a hike and a big lesson all in one. That’s what a good hike can be, at its best.

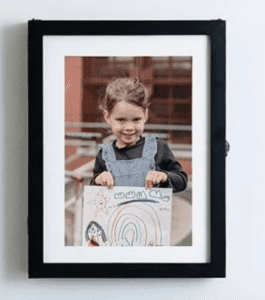

The love of hiking and walking stayed with me throughout my life, and our two kids learned to love it as well.

Here at our home in a remote corner of Vermont called the Northeast Kingdom (NEK), nearby Willoughby Lake is surrounded by beautiful mountains with excellent trails: Pisgah, Wheeler, Westmore, Hor – take your pick. They’re not big like the White Mountains or the Rockies, but the trails are great and views of the lake spectacular.

Unfortunately, those trails have been inaccessible to me for three years now. After inadvertently taking an antibiotic that damaged by tendons (sometimes those warning labels on prescriptions turn out to be true), I had to have a foot surgery. While I regained full function in my foot, the surgery made my left foot slightly wider than my right. This would not have been a problem if I had regular feet, but mine are size 16. I tried shopping for every major brand and there is simply no walking shoe or boot that fits me.

Being unable to go for decent walks or hikes during the pandemic was not good for my overall health. As any wellness professional will attest, a sedentary lifestyle is a recipe for disaster.

I made a promise to myself that I would hike mountains not just with my grandchildren, but with great grandchildren. I’m not hiking anything at present and even walking can be painful.

Well, Winston Churchill said it best: “Never surrender!”

I scoured the Web to find a company that could make me a pair of custom hiking boots that would get me back on my feet and above the tree line once again.

That’s when I discovered Leahy Custom Hiking Boots, a boot maker based in the little town of Felton, California.

Founded and run by Kevin Leahy, the company—and its many positive customer reviews—promised a custom boot like no other. When I read Kevin’s bio I knew I’d found the guy to help me. He’d been apprenticed to a classic boot maker from the Tyrol province of Austria in his early days, and been making custom boots since 1976. The boots shown on the website looked like what you’d see on hikers in the Alps, well-crafted with fine leather.

Kevin’s boots have a classic look.

I immediately emailed Kevin and explained what was going on with my freakish feet. His response was that he’d helped many people with similar challenges—huge feet, small feet, different sized feet. And the feet of people suffering from diabetes or dealing with old war injuries. I ordered my ‘fit kit’ on the spot.

Not long after I received the kit in the mail however, I got an unexpected email from Kevin saying he was going to be visiting a friend on the East Coast, and would I like to meet so he could personally measure my feet?

To me, this was akin to being asked if I’d like to meet the Great Oz. “Sure!” I said.

A few weeks later I met Kevin at the workshop of a colleague of his, Sarah Guerin, in Wakefield, Massachusetts. Sarah, a maker of custom cowboy boots, had connected with Kevin and was eager to learn the secrets of Kevin’s measurement techniques (thank you, Sarah, for hosting the session and taking the photos shown here).

Kevin, 67, welcomed me in and quickly got to work to do a measurement that was far more thorough than anything I have ever experienced. Getting custom boots or shoes made today is a rarity, Kevin explained, but it didn’t used to be. In the early part of the 20th century there were numerous immigrant craftsmen from Europe who practiced the trade, but immigration laws after 1910 greatly reduced their number. At the same time, the mass-manufacture of shoes, pioneered in New England, made cheap but not often perfect fitting shoes the norm. Based on what I’ve seen of Kevin’s skills, I’d say this is a shame. We’ve simply accepted a reality where we’re putting up with foot pain, or simply not walking or hiking at all.

So, sitting in that workshop with Kevin as he set about assessing and measuring my feet, I felt I was going back in time—to a better time—when real fit, comfort and foot health really mattered.

Here is a breakdown of the process.

Step 1: The tracing and imprint.

Kevin tracing my feet.

When I took my shoes off and Kevin looked my irregularly shaped size 16 feet, he said “We’ll definitely be at the upper limits here but we should be fine.” I exhaled, hopeful that this would work.

Kevin started by having me place one foot on a piece of pressure print paper. He had me stand and put my weight on the foot as he traced around it. While the material allowed for the contours of my foot to be traced, it also recorded an imprint on the bottom of my foot that showed darkest where the most weight was applied. Each element of this was another data point that would allow Kevin to perfect the fit.

If all Kevin did was this one thing it would have been more than what all of us have experienced in a shoe store. But it was just the first piece of the foot measurement picture.

Step 2: The foam imprint.

Kevin pressing my feet into the foam.

While I was sitting, Kevin had my raise one foot which he then held and pressed firm into a long plate of foam, leaving an imprint similar to what you’d see if you pushed your foot down into wet sand. When these imprints were complete, I could see each nuanced curve of my feet, including the bunion on the small toe of my left foot that made it impossible to purchase off-the-rack boots.

Here, again, was valuable data to further enhance the perfection of the fit. But as you might have guessed, we had a ways to go. I had let Kevin know in advance about a weak tendon on my right foot. The only way to provide my right foot with enough support is with a high-topped boot that hugs the ankle. That meant another important piece of the puzzle needed to be completed.

Step 3: The fiberglass mold.

Kevin pulling the wet fiberglass over my foot.

As Kevin continued his work, I quizzed him about his early days. After his apprenticeship with the Austrian boot maker, he’d felt hooked to the love of the craft and had kept at it to help all kinds of people enjoy well-made boots. He himself had big feet and knew what it was like to feel foot pain, so this was a real calling for him.

Kevin carefully unwrapped what looked like a white, wet sock. This, he explained, was made of fiberglass, just like what’s used for making a cast.

Unlike a cast, however, in this instance only one layer was required versus a full wrap. Moving quickly so the process could be completed before the fiberglass dried and hardened, he first taped a black strip of paper along the top of my foot and up to the ankle, and over this taped a kind of straw that bulged out. The reason for these two elements became clear only after Keven pulled the wet tube of fiberglass over my toes and up my foot to above the ankle. After a minute to allow this to harden, he used scissors to cut the fiberglass from the toe area to the ankle. Thanks to the strip of paper and straw he’d taped to the foot, he could cut the fiberglass above it without the risk of cutting my foot.

The hardened fiberglass mold.

Kevin held up the hardened fiberglass molds, pointing to the ankle areas and explaining how he’d now have the information he needed to provide full support and a comfortable hiking experience.

I got ready to leave, thanking Kevin profusely, but there was one more important step. And that involved him seeing me take some steps of my own so he could assess my gait and note any irregularities.

Step 4: Observation of ‘normal’ walking.

Me impersonating a runway model. Seeing my gait provided important information for Kevin to perfect the fit.

Kevin asked me to put on my shoes and walk so he could observe my overall gait and note anything unusual that might further inform the creation of my boots. There was a 10-foot walkway outside the workshop. I felt a bit like a runway model—a six-foot six model with gigantic feet—as I did my best to walk normally. Kevin and Sarah looked at me thoughtfully.

“See his shoulders are a little stooped when he walks,” Keven said to Sarah. “You have to look not just at the feet but the whole person and the gait. That matters for the boot.” (I noted this and straightened my shoulders for the next pass.)

“See how his right foot is pronating,” Kevin said, “with the extra ankle support we’ll help prevent that.”

While the in-person boot fit measurement and analysis was done for that day, I learned there was going to be one more important step.

Step 5: The trial boot.

Before Kevin makes the actual boots, he makes a kind of temporary trial boot that customers are asked to wear for a few weeks. There’s a leather insole in the trial boots that over time becomes imprinted by the pressure of the foot. By seeing these pressure points made under real-world use conditions, Kevin can assess if he’s on track with the boots he’s creating, or if he needs to make minor adjustments. Only once the customer sends the boots back to Kevin for this final analysis is he able to make the actual boots.

Given the demand for Kevin’s boots there is a five to six month waiting period. I hope to have my boots by September 2022, and I’ve already started planning my fall hikes up the mountains around Lake Willoughby. The custom boots made by Leahy boots are not cheap, but they will likely last a lifetime. And, for me, being able to hike again—especially with my kids and grandkids—is priceless.

I’ll post an update later this year. In the meantime, check out Kevin’s website to learn more. I’m sure he’d be happy to answer your questions and help you get the kind of boots you’ve wanted but could never find.